Stick Dancing:

Seiji Ozawa and Mahler’s Third Mark

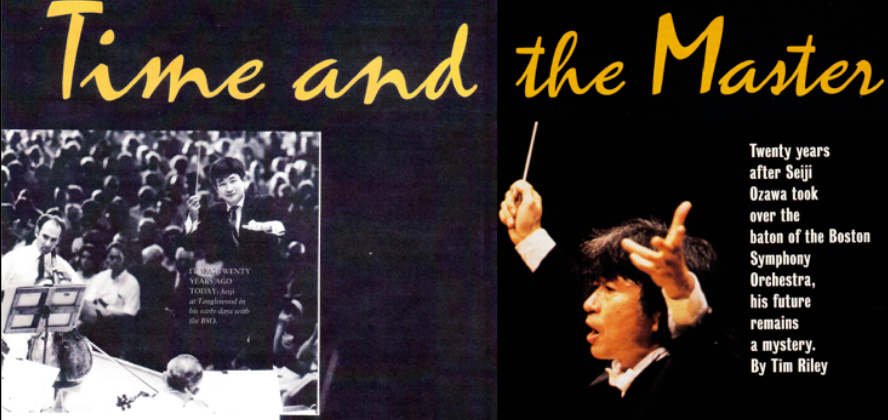

20 Years with the Boston Symphony Orchestra

“Time and the Master” (Boston Magazine, 1993)

FOR THE FINAL program of his twentieth season last spring, Seiji Ozawa chose Mahler’s Third Symphony, a piece so difficult that even Ozawa’s mentor, Berlin’s imperious Herbert von Karajan, had purposely avoided it. Ozawa was undaunted. At 57, the conductor still showed up for rehearsal in his white ducks and soft sandals, and he still led the Boston Symphony Orchestra with a mixture of politesse and intensity.

In some ways, the Mahler program epitomized the tensions of Ozawa’s controversial two decades at the BSO’s helm, a tenure marked by public acclaim, local critical ambivalence, and enough backstage intrigue to fill up several British tabloids. With a last-minute cancellation by mezzo-soprano soloist Birgitta Svendén, the Mahler rehearsals were anything but routine. To replace Svendén, three different soloists were hired, requiring last-minute scheduling changes.

Ozawa was not just closing the season, he was mounting one of the repertoire’s most demanding pieces from memory and taking it to Carnegie Hall. On top of that, the accompanying recording sessions for this piece would complete the BSO’s decade-long Mahler symphony cycle for the Philips label. At the end of a season marked by uneven playing and thorny contract maneuvers, the stakes could not have been higher.

Ozawa had only four rehearsals in which to reconquer the massive, 100-minute symphony. The rehearsal on Thursday morning, April 22, offered the last chance the BSO forces—more than a hundred strong—would have to play through the entire score. The orchestra seemed restless. Ozawa called out last-minute directions while the players ran through each movement. Each time the conductor stopped the piece to speak, his musicians fell into nervous chatter.

Ozawa proceeded aggressively. While the orchestra played, he announced the number of beats per bar he would be conducting in the difficult slow movement and demanded strict adherence to the tempi he had set in sections where the musicians tended to rush or slow down. Even at his most annoyed, he interrupted his players with only a brusque, “Excuse me, excuse me.” Ozawa guided the orchestra through dozens of rhythmic snares and abrupt transitions while a digital clock above the percussionists quietly counted down.

That evening, in front of a packed house for the first of the six Mahler concerts, the BSO sounded like a different orchestra. With Ozawa conducting in front of a closed score, the frayed rehearsal atmosphere was replaced by triumphant music-making. Suddenly, this most difficult and searching of Mahler marathons rose to a level of beauty and mystery that had barely been hinted at during the rehearsals.

Instead of rambling on and on in a halfhearted run-through, the music floated by, one glorious section flowing into another, impelled by the kind of emotion that technique alone doesn’t explain. The audience stood up. They roared. The critics lavished praise upon Ozawa for returning to form with such a huge, unruly piece of music.

At the end of Ozawa’s twentieth season, the Mahler Third summed up his relationship with the BSO in ways all the backstage talk couldn’t. Ozawa’s Mahler was some of the best playing the orchestra had done all year—it ranked up there with its recent Mahler Ninth, which some cite as Ozawa’s finest hour. It was the kind of musical peak that posed new questions for the conductor: Would Ozawa’s musical growth ever match that of the orchestra he had by then largely appointed? Would he ever consistently make music as provocative as this Mahler performance? For that matter, why didn’t his music-making consistently reflect more of his complex interaction with this orchestra?

As he begins his twenty-first year with the BSO, Ozawa holds the longest tenure of any music director of a major orchestra still conducting. While some other orchestras are breaking in new conductors (the New York Philharmonic, Kurt Masur; the Chicago Symphony, Daniel Barenboim), Boston is entering its third decade with Ozawa, whose stint with the BSO seems likely to surpass even Serge Koussevitzky’s 25-year reign, from 1924 to 1949.

For many, though, Ozawa’s tenure remains in the shadow of Koussevitzky’s legacy, especially when it comes to commissions of contemporary works. Ozawa’s two decades have been marked by an unusually high level of controversy and public bickering. Critics regularly assail his weakness in conducting key composers such as Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, and many say that he has not lived up to his early promise. The orchestra’s management is accustomed to being on the defensive about its maestro, repeatedly calling Ozawa “one of the world’s greatest conductors.”

The front office recognizes that there is a problem but concedes only that Ozawa’s international touring schedule and commitments to his native Japan often conflict with the best interests of the BSO.

The most compelling complaints come from the members of the orchestra itself. The BSO’s players, among the most talented musicians in the world, routinely fault Ozawa’s musicianship, citing his uneven attention to detail, his inability to blend the brass sound with that of the rest of the orchestra, and his interpretational blind spots. Many also criticize his administrative and interpersonal skills.

One orchestra member claims that some of the players suffer from long-term fatigue, and many agree that the best music of any season is performed under guest conductors. The outspoken unhappiness of some of the BSO’s players led last season to the longest contract dispute in the orchestra’s 112-year history.

Professional orchestra players are inveterate complainers by nature, and some of history’s most revered conductors (the Cleveland Orchestra’s George Szell, for example) were despised by their musicians. Comments from BSO players are sometimes colored by opposing agendas and petty politics. Furthermore, by any objective reckoning, the orchestra has boosted both its level of musicianship and its international status under Ozawa. Today the BSO is widely recognized as a better orchestra than it was when Ozawa took over.

During his 20 years as music director, Ozawa has appointed more than 55 of the orchestra’s current lineup, making it as much his own as it ever was Koussevitzky’s or Charles Münch’s. (The last of Koussevitzky’s appointments retired at the end of 1991.) And although some commentators say that his talent for opera overshadows his gifts in the symphonic repertoire, others point out that Ozawa’s staged operas (like last year’s Falstaff) have been the high points of recent seasons and that any conductor has strengths and weaknesses.

When it comes to strengths, Ozawa’s masterly stick technique is undisputed, and lauded by both admirers and detractors.

“He conducts as though he were born with a baton in his hand,” says violinist Tatiana Dimitriades, who has been with the BSO for seven years. “Ozawa’s gestures are so watchable; he’s so animated and so clear. Seiji is a very honest musician. Unlike a lot of maestros, he has no pretenses—he believes in what he’s doing.”

Concert audiences respond strongly to Ozawa’s gift: his graceful, dancer-like presence on the podium makes BSO concerts fun to watch. And although he rarely smiles while conducting, he conveys an impish charm through the music, especially music with intricate rhythms, that persuades people to buy up more than 90 percent of a given season’s subscription concerts—an achievement other orchestras envy.

His podium manner is so appealing, in fact, that his appointment to the BSO in 1973, when he was 38, touched off a wave of Oriental chic. “It was like a roar would come out of the audience” for him, said violinist Marylou Speaker Churchill in 1986. “The audience loved looking at him. Visually he’s very satisfying.”

For a Brahmin institution like the BSO to hire this young conductor away from the San Francisco Symphony was a tremendous risk, but it was one that both management and trustees feel has paid off. Orchestra players, of course, consider themselves more astute judges of Ozawa’s talents, and they see management as concerned less with Ozawa’s musicianship than with his ticket sales and his high-profile contracts with major labels such as Philips, RCA, and Deutsche Grammophon, which employ the BSO for major recording projects.

One player says that Ozawa’s English is “as good as he wants it to be.” The player recalls a particularly tense confrontation with the entire orchestra on the rotation issue last fall, during the BSO’s tour of South America, when Ozawa defended his position in terrific English.

Many of those projects enlist Ozawa to conduct for the major soloists of the world, such as cellist Yo-Yo Ma and violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter. The Boston Globe’s classical music critic, Richard Dyer, initially one of Ozawa’s harshest critics, thinks this is no accident and compares Ozawa’s accompanying talent to that of Eugene Ormandy, the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1938 to 1980, who was widely seen as the best concerto conductor of his era. Ozawa appears to be gaining a similar reputation, Dyer contends, pointing out that it enhances the BSO’s prestige to be an orchestra that many major soloists record with.

Ozawa has also attracted major corporate sponsorship for the BSO. NEC, the Japanese electronics giant, has supported several BSO tours of Japan and will sponsor this year’s European tour. Bank of Boston, Gillette, and NEC sponsored last year’s South American tour. Nikko Securities sponsors the Boston Pops and funded a third Pops tour of Japan last June. Last season also saw a remarkable contribution to the BSO from one of its own active members. Bassist Joseph Hearne (and his wife, Jan Brett, a children’s book author and illustrator) endowed the BSO with a chair named for his stand partner of 31 years, Bela Wurtzler, who has just retired. The endowment amounts to $250,000, an unheard-of donation from an active member of an orchestra.

As for Ozawa’s short-comings—at least from a Boston-centric viewpoint— the demands of his ambitious international touring schedule are known to rankle orchestra management. He regularly conducts the Staatsoper and Covent Garden. And his allegiance to Japan—where he raised his two children—also demands much of his time and talent. In 1992 Ozawa founded the Saito Kinen Festival in Matsumoto—nestled in the “Alps of Japan”—which he named after his beloved teacher Hideo Saito. He has been conducting the Saito Kinen Orchestra since 1984.

Ozawa’s workaholic tendencies have taken their physical toll: his body has begun to protest in recent years with his shoulder tendinitis. Last season alone Ozawa made his acclaimed Metropolitan Opera debut in December with Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin; released several recordings with the BSO, including Tchaikovsky’s opera Pique Dame (again to critical acclaim); and conducted the Saito Kinen Festival’s production of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex, which premiered on PBS’ “Great Performances.”

Such globe-trotting would be taxing even for a conductor who didn’t have a “home” orchestra. Despite all of Ozawa’s traveling, however, Kenneth Haas, the BSO’s managing director for the past six years, says that in an average season the conductor spends more time with the BSO (over 22 weeks, including 6 at Tanglewood) than any other American music director has spent with his or her orchestra. Despite Haas’ claim, BSO management is known to cross swords with Ozawa’s New York manager, Columbia Artists’ Ronald Wilford, over Ozawa’s timetable. His tour of Japan with the Vienna Philharmonic this fall practically coincides with the BSO’s own European jaunt in December, prompting numerous complaints within the organization.

“Taking the Vienna Philharmonic to Japan raises hell with our schedule this fall,” says George Kidder, the frank president of the board of trustees. “It will mean he’s cramming to prepare the BSO for its own European tour. He’s actually going to be coming back from Japan via Paris, where he’ll rehearse the chorus, and then meet up with the orchestra in London for rehearsals there before the tour begins.”

Kidder also expresses disappointment that the Saito Kinen Festival conflicts with Tanglewood: “That festival he’s running in Japan interrupts his last weekend at Tanglewood. We don’t want another conductor overseeing those last concerts at Tanglewood, when some BSO players are going to retire. I wish he’d move his schedule back and make room for that.”

The BSO’s players, who generally gripe about Ozawa’s musical failings, administrative passivity, and inefficient rehearsal habits, also have more specific criticisms of his musicianship. Ozawa can be fun to watch, most of them concede, but music is about sound, they point out, and Ozawa’s music doesn’t measure up to his gestures. Others complain that Ozawa has such a keen rhythmic sense that he loses sight of what’s called “line,” the directional phraseology of the music.

“He’s what some musicians call a top-liner,” explains Boston Herald classical music critic Ellen Pfeifer. In other words, she says, “what he understands about a score is the violins, the melodies. But I don’t think he’s all that superficial. When there’s a big mass of sound, he tends to give you everything at once, no foreground or background. I’ve written that over and over again.”

Another criticism holds that while Ozawa is a good coordinator of large-scale works by Mahler and Strauss, as well as romantic and contemporary opera, he has trouble with the subtlety and styling required for a finer classical repertoire.

“He tries very hard with Mozart and Haydn,” says one string player. “But he doesn’t know the meaning of the word elegant. He doesn’t have classical ideas about sound. Elegance and charm—he doesn’t know from that. That’s a terrible thing to say, and I feel bad saying it, because he hired me. It’s not like he’s not trying; he’s just barking up the wrong tree, looking for answers in the wrong places.”

Another issue clouding Ozawa’s two-decade milestone has been the hiring of a principal flute player to replace Doriot Anthony Dwyer, who retired at the end of the 1990 season. Over the past three years, Ozawa and the BSO audition committee have heard dozens of auditions. Ozawa finally offered the place to Tim Hutchins, the first flutist from the Montreal Symphony Orchestra. But Hutchins’ orchestra made him a tempting counteroffer, and he couldn’t be lured to Boston. Now acting principal flutist Leone Buyse has accepted a teaching position at the University of Michigan, and the first-flute spot will be filled this season by free-lance guests and more audition finalists until a permanent replacement is found. Some worry that the longer the seat remains open, the more potential flutists will get the impression that the job is not only unattainable but undesirable.

The BSO is, after all, a business, and playing in a world-class orchestra can be a grinding job at times—not simply about making great art. Before one of the Carnegie Hall concerts, one cellist put it bluntly: “If you’re a section player looking for complete artistic satisfaction from this job, you’re full of shit.”

The issue that loomed larger than any other during Ozawa’s twentieth season with the BSO seems minor to outsiders, but it was central, and symbolic, to the orchestra’s music and morale. For more than 15 years, the BSO string section has had a revolving-seats policy that rotates individuals at the back of both the first and second violins, allowing different seating assignments for players on successive programs. Intended as a morale booster, the policy was designed to prevent players at the back of the second-violin section from feeling stuck there. The first three stands of the first violins and the first two stands of the second violins remain static and are filled only by special audition. The remaining seats in both sections rotate. This means that even if a player is hired as first violinist, he or she will sometimes play in the second-violin section. It also means that second-violin players may receive equal time at the back of the first-violin section.

Instituted under Ozawa back in the late ’70s, this system is still revolutionary: no other major orchestra in the country uses anything like it. For the past several three-year contracts, however, Ozawa has talked about phasing out the rotation policy on musical grounds. To his ears, the experiment has not worked. He—and others—feel more cohesion was needed from the violins, more ensemble teamwork over time. As a result, management offered the orchestra a contract last fall that included provisions for phasing out the system.

The players’ committee unanimously recommended that the orchestra sign the contract despite the players’ unhappiness with the phaseout provisions. But the orchestra balked—and returned the contract to the players’ committee to renegotiate with management. The negotiations continued until March, when the players finally decided to accept the compromise of “block rotation”—two to three players rotating at once—suggested by the cello section.

For much of the season, the orchestra “played and talked”—that is, played without a contract while negotiations were held. The issue quickly galvanized feelings about the conductor.

“It became a referendum on Ozawa,” admits Kidder. “And we insisted that Ozawa be a part of wrestling with this string-rotation issue at the table with the orchestra members. He sat in on five different working sessions on this issue, and he impressed the players with his commitment to working it out. And now we have three years to look over this compromise—’block rotation’—and Ozawa will be part of the next negotiations.”

Ozawa has enough political savvy to realize that a certain amount of saber rattling occurs during any contract negotiation and that not every vote against the contract should be counted as an anti-Ozawa vote. He also knows that the remaining “big five” orchestras—Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York—look over the shoulder of their own local musicians’ unions whenever a BSO contract is renegotiated.

According to some members of the orchestra, the players’ committee last year was stacked with people who wanted to oust Ozawa, and they turned the string-rotation matter into a convenient wedge against management to protest the contract.

Ozawa spoke candidly about this sensitive subject in his office. “It should not be contract issue,” he said. “BSO string rotation still unique, not one other orchestra has tried it, or if they did they didn’t continue. I like system, and the pioneer spirit is wonderful. Only problem is, as contract issue, it became inflexible.” (One player says that Ozawa’s English is “as good as he wants it to be.” The player recalls a particularly tense confrontation with the entire orchestra on the rotation issue last fall, during the BSO’s tour of South America, when Ozawa defended his position in terrific English.)

Ozawa claims to be unruffled by the long negotiations necessary to hammer out a compromise—the longest period of “play and talk” in the orchestra’s history. “Six months is short to sort out this complex a problem,” he said. “We are doing very unique thing. It took many meetings, very emotional exchanges, and I have good feeling about result. Logically, every violinist is considered equal. But I give three-year trial period, because we not ready to say “Okay, this is it.'”

Ozawa called the “block rotation” compromise progress: “Violinists believe this will make their life much more musically interesting. And I say this, and this is something delicate to say: I know very well that to spend life at back of second-violin section could be miserable. But many orchestras have better second section in the violins and pride. They play as they think, “We are the best second violins in the world—we even better than first violins”. Certainly, I conduct other orchestras with this attitude. We may create that situation here.”

Other underlying issues include some players’ unrealistic expectations. The BSO is, after all, a business, and playing in a world-class orchestra can be a grinding job at times—not simply about making great art. Before one of the Carnegie Hall concerts, one cellist put it bluntly: “If you’re a section player looking for complete artistic satisfaction from this job, you’re full of shit.”

The best guess about how long Ozawa will remain in Boston seems to depend on whether a major opera house offers him a post. “If an opera company were to ask him to be their director, he would jump at it,” says the Herald’s Ellen Pfeifer.

Richard Dyer believes that the idea of ousting Ozawa gets more difficult when you look at the list of possible replacements. “The list of people who might be better than Ozawa as a music director of the BSO is very short, and it’s getting shorter. You have to deal with questions like, where does a family man like Simon Rattle want his kids in school? If any orchestra could get Rattle, it’s this one.”

Contributing to Ozawa’s defense, Dan Gustin, the BSO’s assistant managing director, says that although “he has made enemies in the orchestra, Seiji hasn’t hidden behind the board or management. He’s stood there alone and taken some strong positions, like on this string-rotation issue. Some people think he’s taken the wrong positions. But that’s what a conductor does.”

Ozawa himself, in a TV documentary, has described his relationship with the BSO as a “marriage—and marriages are supposed to end in death.” His remark suggests that he has no intention of leaving. Considering how fragile marriages can be, especially those in which the parties wrestle with competing professional concerns, the analogy seems apt.

“This is a lonely job,” Ozawa says with a sigh. “I have to be lonely—that I learn over the years.”