Sample Chapter: Charlie Rich

on the rebound

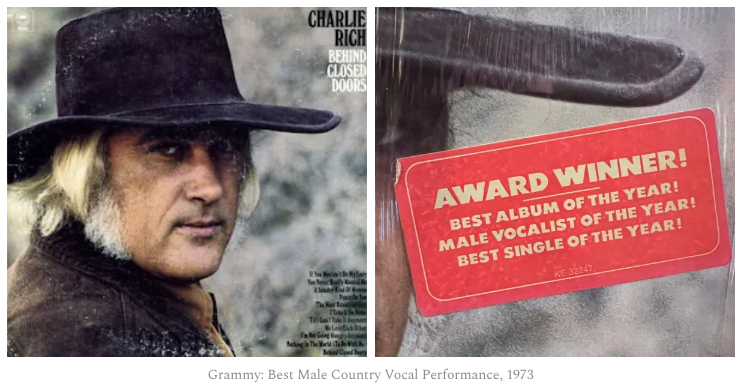

Charlie Rich, Behind Closed Doors (Epic, 1973)

CHARLIE RICH PUSHED hard against everything wrong with the music industry and came to embody everything that’s right with C&W. Fresh out of the Navy in 1956, Rich played piano for Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis at Sun Studio in Memphis. But once producer Sam Phillips stuck Rich in front of the mike, he never rode the big Elvis coattails like the others. Phillips gave Rich’s silken voice his best shot for five years with only modest success, even though rock sage Bob Dylan called Rich his favorite singer. In all, Rich toiled away for seventeen years before releasing this middle-aged country classic in 1973.

C&W has a well-known weak spot for middle-age ennui. But with this quiet breakout, which spent over a hundred weeks on the charts, Rich authored the third-biggest selling album of the ’70s. His own heartache was more professional. He had his first hit in 1960, with “Lonely Weekends,” but the follow-up, “Mohair Sam,” took him five years. This was in part because Rich was a true eclectic, and part because he was known to tip a few. Behind his own closed doors he seemed happy enough. His bride, Margaret Ann Rich, wrote “A Sunday Kind of Woman,” “Life’s Little Ups and Downs,” “You Never Really Wanted Me,” and “Nothing in the World (To Do With Me),” the kind of songs it takes a lover to compose for her husband. Rich’s intimacy made a completely different kind of sense when he sang something by her.

You can still hear Rich redeem every country cliché he was so uncomfortable with; his breakthrough, so long in coming, only told him that he’d been on the right path all along. vocal holds in reserve.

It took Nashville’s Billy Sherrill to ferret out what everybody else was missing, and by then it was 1967. Sherrill had Nashville’s golden touch: writing and producing for Tammy Wynette, George Jones, and Glen Campbell. He churned out countrypolitan velour like so much vinyl siding. Even so, it took him six years to score Rich’s breakthrough, and then on a number that recast him as someone who found salvation through lust. This luminous digital transfer lives up to its material. In many of these songs, Rich casts an eye over what makes love go right or wrong and what it tells him about himself. It’s a spry allegory for his guarded passion about country music, both professionally and aesthetically. In “A Sunday Kind of Woman,” he’s in awe of how a woman of elegance can love a man of disrepute. But he’s also singing about how C&W embraces a guy who feels vexed by pop and his ambivalence about the kind of club that would have him as a member.

On live television at the Country Music Association Awards in 1975, Rich announced John Denver as Entertainer of the Year before torching the winner’s card with a pocket lighter. Listening to Behind Closed Doors after almost thirty years, you can still hear Rich redeem every country cliché he was so uncomfortable with; his breakthrough, so long in coming, only told him that he’d been on the right path all along. In the title song, sexual discretion becomes a metaphor for how much Rich’s poised vocal holds in reserve. The jazz pianist turned rockabilly fool had his own weak spot for country’s abiding uncertainties. He turned world-weary lust into a class act—a country theme if there ever was one.