Sample Chapter:

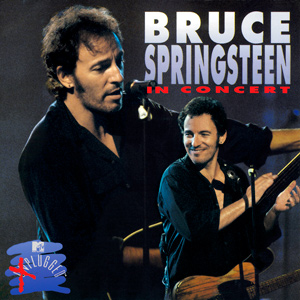

Bruce Springsteen

Falling Behind

In Concert/MTV Plugged, Bruce Springsteen

CD Review Magazine, March 1993

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN’S FAITHFUL throng has swallowed disappointment ever since its Boss released Human Touch and Lucky Town a year ago. Beginning with an underwhelming appearance on Saturday Night Live that introduced the core of his new band and a live radio broadcast that sounded more like a rehearsal, Springsteen’s stock has plummeted. At the end of his radio broadcast, he joked about how quickly his albums had slipped down the charts. You had to smile at how he was able to kid himself about being outsold by “Weird Al” Yankovic, but you also had to admit that the old Bruce always seemed above such commercialism.

Now comes In Concert, the laserdisc to his November 1992 MTV Unplugged appearance, which was released in VHS format in time for Christmas. Laserdisc owners are supposed to rejoice that the laser release includes an extra song (“Roll of the Dice”) and remains uninterrupted by Marky Mark’s underpants pouting or Candice Bergen’s long-distance sarcasm. But the program poses Springsteen squarely in the shadow of Eric Clapton’s Unplugged sales juggernaut, which will only erode his star capital further. Springsteen is one of the few rock songwriters who invents character and narrative. At his best he writes about himself through the eyes of fully imagined people. But the strengths of Human Touch and Lucky Town lie mostly in where their ballads echo the burnished anxiety of 1987’s Tunnel of Love (Springsteen’s own Blood on the Tracks). The acoustic numbers on this laserdisc make you wish Springsteen had turned in a genuine unplugged set the way he did for Neil Young’s Bridge School Benefit in 1985 or his Christic Institute sets in November 1990 (both widely bootlegged and solo outings that reimagined the Dylan model). So take advantage of the laserdisc format. Program your disc to play “Red Headed Woman,” “Growin’ Up,” “Thunder Road,” “My Beautiful Reward,” and “If I Should Fall Behind,” and you can imagine what a real unplugged set might have sounded like.

As it is, after years of pining for the great Springsteen concert film that would rank with Stop Making Sense, or even Sign o’ the Times, we get a slick, uninspired performance from a young band with full complement of backup singers, and almost none of it tempts the newcomer into what makes the Boss great. It seems that manager Jon Landau has lost his magic touch to at least the same degree that Springsteen has underestimated his audiences with his new songs and players. Let’s take the issues one by one. The classic rock’n’roll band used to mean a group of individuals who could invest in a song with more than mere professionals might by simply hitting the right notes. Especially with his E Street Band, Springsteen raised the stakes for bands everywhere by pulling more from his Jersey chums than anybody had a right to. You came away from Springsteen shows of old bowled over by how deeply his songs cut, given that the level of musicianship in many players was decidedly limited.

Working hard not to upstage Springsteen, he comes across as a young buck who knows he’s hit the jackpot, and all he has to do is ride out his luck without making any major mistakes before he can retire.

Now the Boss has hired a bunch of young L.A. turks, distinguished in the main by drummer Zachary Alford, who toured with the B-52s. Retaining E Streeter Roy Bittan seems largely a sentimental move onstage, even though Bittan has long been his most musical cohort and sometime co-producer. Bassist Tommy Sims is solid but indistinctive. Guitarist Shane Fontayne is the main distraction. Long before G.E. Smith primped and mugged his way through countless Dylan shows, the role of the lead guitarist had become an overly self-conscious exercise in pretty-boy mane-tossing. Fontayne, a member of the final iteration of Lone Justice, is certainly a fine player, but some guitarists are simply annoying to watch. Working hard not to upstage Springsteen, he comes across as a young buck who knows he’s hit the jackpot, and all he has to do is ride out his luck without making any major mistakes before he can retire.

Yes, the men’s-movement duet with Bobby King, “Man’s Job,” gives the show some topicality. (Why doesn’t he just hire Robert Bly to bang the congas and get it over with?) But nobody’s going to place this song above “Walk Like a Man” for sheer insight into the male psyche, and as masterful a singer as Bobby King is, the set-up is simply too tempting. Compared to the missing Big Man, saxophonist Clarence Clemons, King has a pint-sized stage personality. These band problems seep into the material. “Lucky Town” is easily the most arresting number of the lot, a gambler’s flight clipped by the hard irony of the refrain, which rears back on the song’s fantasy like a horse suddenly refusing to jump the fence. Springsteen knows just how to push this song—it falls forward with hard-won grit. Along with “Light of Day,” a soundtrack throwaway that survives its hokey guitar duel, it’s one of the rare moments when the band and its material seem suited to each other.

Elsewhere, the show can be divvied up between the new songs that sound overwrought and overplayed and the old songs that seldom fail. “Growin’ Up,” a former rave-up from his debut album, has ripened into a fond reminiscence of high school that gets as much mileage out of adolescence as “Born to Run” ever did. And, in an ironically celebratory “Atlantic City” (from Nebraska), the band glimpses some unexpected pockets of terror and violence.

The net effect of these current Springsteen shows is of a master entertainer going through a transition he doesn’t have a grip on yet. Maybe some autobiography is in order: imagine a song about how it feels to have a fulfilling marriage compete with an ongoing career scrambling to find its new place in the world. The faithful still have hope, and you could argue that these current albums constitute the lull due any such careerist on his way to better days. But what it reveals about everything we once adored about the Boss is more fretful: that he’d rather lead a band now than be a part of something even bigger than his music; that his new “family man” persona precludes living up to his talent; that his relationship with his audience, once triumphantly meaningful, has now leveled off to a series of near-rousing entertainments.