Book Excerpt: What Goes On

All I’ve Got to Do

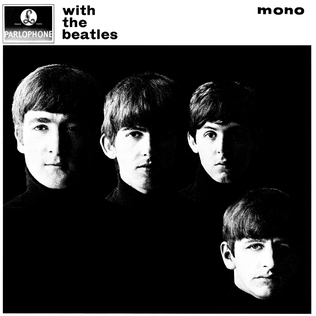

Recorded September 11, 1963 for With The Beatles

—an exploration of the narrator’s attitude as colored by shifting syncopations and major/minor mood swings.

All pop songs contain an imagined speaker and audience, a singer (“I”) who tells a story to an implied listener (“you”). Both these imaginings flow from a real author, the song’s composer, who may or may not inhabit a fictional persona.

These factors come into play when considering “authorial voice” in Beatles songs even before contemplating how the Lennon-McCartney partnership breaks down. Does the singer address a secondary imaginary subject or the listener directly? How do so many of these early Beatles songs deploy the emphatic personal pronouns with such intimate candor? In a harmonized melody, do two voices split from single consciousness into different layers of a single author’s psyche?

Lennon’s lead vocal in “All I’ve Got to Do” drips with irony: his lyrics express confidence; his delivery broods with insecurity. His words boast of boundless confidence in the sturdiness of love; his vocal leaks torment. In the opening moments, that questioning guitar arpeggio of an augmented triad plus added ninth and eleventh undermines the singer’s opening statement: “Whenever I / I want to kiss you, yeah.” And the band’s stop-and-start rhythms, yoked by Ringo Starr’s tight syncopations, frame the singer’s resolve in uneasy, shifting patterns (forecasting similar strategies in “Any Time at All” and “In My Life”).

In verses, the singer starts on a minor chord (“Whenever I”) and swerves toward major (“I want to kiss you, yeah”). (The lead melody and, when harmonized, the descant part, are drawn fully from the E major-pentatonic scale, E-F<sharp>- G<sharp>-B-C<sharp>, despite augmented and minor colors for a subtle modal intrigue in the vocal interaction with guitars.) In the bridges, this pattern reverses, from major (“And the same goes for me . . .”) to minor (“I’ll be here yes I will”). This tension between major and minor conveys the uneasy mood vexing the singer, where his fervor rides on currents of dismay and insecurity (and resembles the following year’s “No Reply,” wherein he will try to convince himself of his own resolve during bridges). Other songs that deploy this major-minor tension between contrasting song sections include “I’ll Be Back,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “I Should Have Known Better,” “Things We Said Today,” “Girl,” “Wait,” and “Fixing a Hole.”

With so many tight spaces, so many falling vocal lines trailing off into exasperation, so much withheld tension vying for release in the bridges, the ensemble sustains the singer as he fights for air (0:48, and again at 1:28 when Lennon skids right off the melody as the others carry him). There’s a crimped, desperate quality to this track that carries a dark emotional quandary, where no amount of rallying can puncture the mood. Note how each bridge closes with a declaration of major tonic- chord confidence (at 0:59 and repeated for emphasis at 1:39) and then dissolves right back into the stop-and-start hedging of verses. Finally, all the constriction and denial leaves the listener with the sense that none of the clever harmonic manipulations and concluding reassurances (“You just gotta call on me”) can scratch the song’s itch.