Book Excerpt: What Goes On

If I Fell

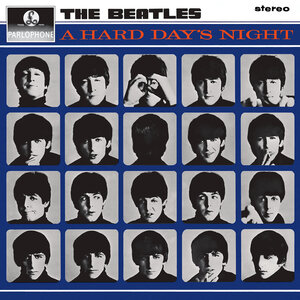

Recorded February 27, 1964 for A Hard Day’s Night

—working through an authorship mystery in Lennon and McCartney’s most celebrated vocal duet, conveying the poetic text’s caution based in the pain of the past.

The Lennon and McCartney songwriting partnership presents intriguing emotional riddles. Early on, we think they collaborated quite closely, each contributing lines and sections to each other’s song drafts. But even then, they had an unusual arrangement: they agreed to share legal and financial credit even if only one had composed a majority of, or even a complete, song. This gave them each great freedom to work alone or together, and help one another with simple fragments or fully formed drafts. As they develop throughout their career, you can hear them growing apart both in terms of subject matter and in the way their distinctive duets give way to vocal solos. The late vocal duets carry distinctly different creative moods than their earlier, closer harmonies.

Only they know who contributed what to which songs, but the guiding principle judging authorship stems from who sings lead. “Strawberry Fields Forever” has a Lennon lead with no vocal harmonies from others, typical for the middle period. It’s the kind of song McCartney could never have penned. In fact, a week after Lennon presented it to his partner, McCartney came back with his answer: “Penny Lane,” in which he sang lead with no harmonizing.

With early Lennon-McCartney songs, scholars still dissect which strands belong to which partner, often futilely. In hindsight, we hear “If I Fell” as the first in a string of Lennon confessionals that includes “I’m a Loser,” “Help!,” “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” “Norwegian Wood,” “Julia,” “Because,” and “Don’t Let Me Down.” “If I Fell” poses the ultimate example of this authorship riddle: Lennon sings lead only on the introduction, the number’s harmonically deceptive eight-bar soliloquy. (One <flat>II chord, a triadic jazzy tritone substitution for the local dominant, first helps tonicize the leading tone and in a second phrase is reinterpreted as the tonic itself.) When the verse begins, it slips into perpetual duet: “If I give my heart to you” (at 0:18–24) sung in harmony (McCartney leading on the upper line, Lennon on a lower harmony part), and “I must be sure” (at 0:25–27) in unison (same notes sung by both singers). Should we presume to call this song a closer collaboration than, say, “All My Loving,” where McCartney sings lead through most of the song with only faint backup vocals from Lennon and Harrison in the chorus (and a double-tracked descant addition to the final verse)? Perhaps. (In surviving demo tapes of “If I Fell,” Lennon takes the upper vocal melody in verses, and the lower line in bridges, so at least as far as these vocals go, their collaboration involved working out vocal parts as part of the composition.) These authorial questions frame the song’s larger subject: the free-fall insecurity of leaping headlong into an affair.

This duet from 1964’s A Hard Day’s Night soundtrack traces poetic threads of the Lennon-McCartney partnership expressed as both promise and peril. Lennon sings the preamble, teetering between commitment and reluctance, and the song spins out indecision through intricate vocal lines.1 For the verses, McCartney’s upper line ducks and glides with geometric lyricism. Each individual line would have made a sturdy melody on its own, although the upper part is tonally more often goal-directed; combined, they trace a poetry of uncertainty.

The lyrics describe love’s oscillating, intemperate swells, seeking comfort and reassurance where only risk abides. The narrator describes wanting to make a commitment to his new lover while recounting the humiliation of his lingering broken heart from a previous romance. This confounds the typical romantic narrative, where a suitor pledges devotion while praising and flattering his subject. In this song, the singer can barely contain his hurt (regularly invoked by the mixture-induced minor iv chord, first in Harrison’s twelve-string turnaround at 0:38, later coloring both the bridge and coda) while considering a new commitment. The appeal to the subject stems mainly from the singer’s candor: you should know I’m still hurting from a recent breakup; can you reassure me that you won’t jilt me too?

In a mistake that hardcore Beatles fans cherish, McCartney actually chokes on a high note on the word “vain” during the second bridge (1:44). In the mono mix, this mistake was “corrected” with the previously performed true note spliced in (1:11). But in the stereo mix, this crack remains as sung, only intensifying the song’s sentiment: the emotional pitch of the song actually brings the suitor to a breaking point while expressing fear that his love might be “in vain,” all for nothing. Was a ballad ever so fluid yet tough-minded? Would two harmonizing writers ever sound as timidly poised?