Book Excerpt: What Goes On

Strawberry Fields Forever / Penny Lane

Recorded in November 1966 for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Paul McCartney spent the fall of 1966 on safari in Kenya and writing the soundtrack for The Family Way—the first music to be credited to a solo Beatle.4 Lennon also had a film role, acting in How I Won the War, shot in Germany and Spain that September through November. Harrison studied sitar under Ravi Shankar in Bombay and toured the Indian subcontinent. Ringo Starr caught up with family at home in Surrey. Lennon in particular seemed at odds with himself; the group he’d led for nine years was disintegrating with no goals in sight. Because John used his art as an emotional release—as he acknowledged doing in “I’m a Loser” and “Help!”—the deeper identity crisis that overtook him in the fall of 1966 might have brought him to a similarly productive catharsis. He picked up a nylon-string classical guitar in Almería, Spain, churned over his nagging childhood emotional trials, and began composing “Strawberry Fields Forever.” As the composer said himself, “‘Strawberry Fields’ was psychoanalysis set to music, really.” Such an inspiration for his anguished work would be an early parallel of the Beatles’ final dissolution in 1970 leading to primal screams for help on the Plastic Ono Band album.

When Paul heard “Strawberry Fields,” he decided to write his own song memorializing childhood memories, all situated in the popular bus roundabout known as Penny Lane. The Beatles devoted several weeks at the end of 1966 to recording “Strawberry Fields Forever” and followed this by taping “Penny Lane” and a very early McCartney composition, “When I’m Sixty-Four,” recently completed in honor of Paul’s dad’s sixty-fourth birthday. All of these tracks were initially intended for some future album, but EMI and Capitol insisted they put out a single to break up the lull between releases. They chose two tracks and designated each as A-sides (both directed for radio play), “Penny Lane” / ”Strawberry Fields Forever.” Because both songs circled childhood with contrary tones, critic Greil Marcus dubbed this “the first concept single.”

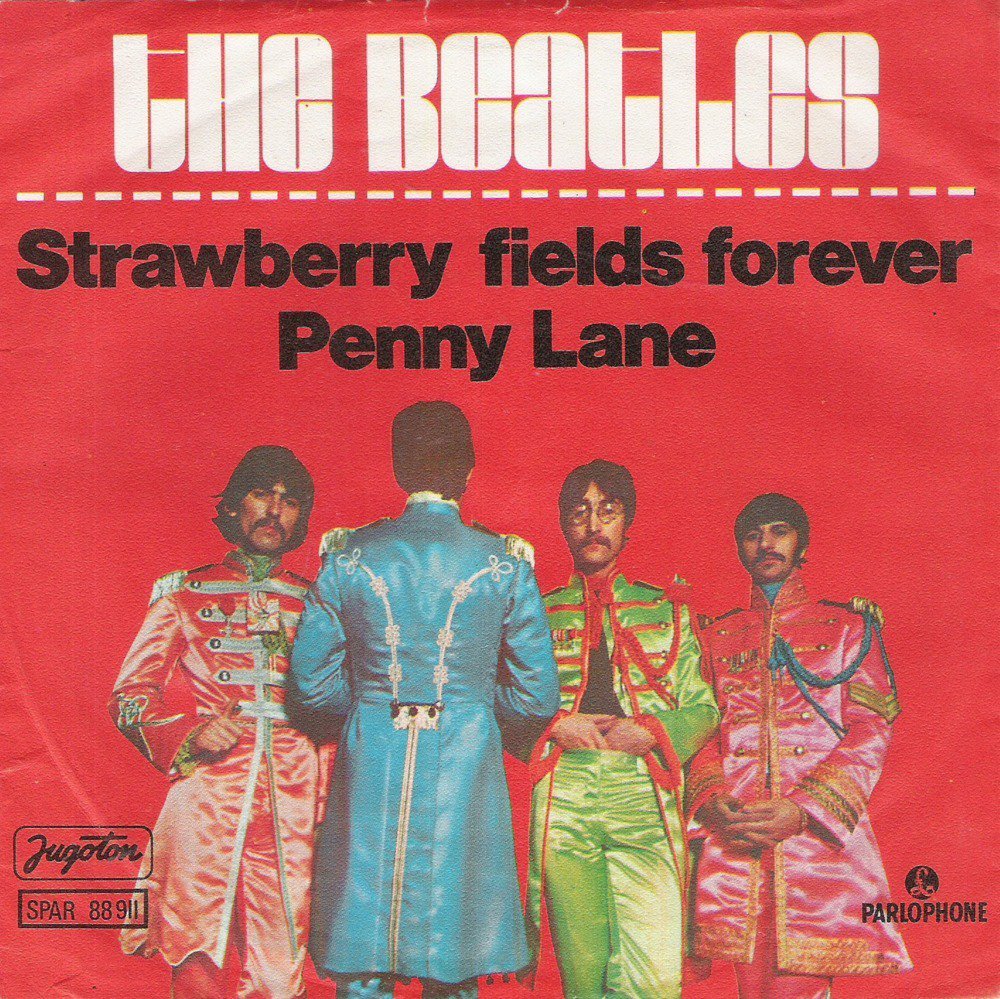

When “Strawberry Fields” was released with “Penny Lane” in February 1967, listeners swung helplessly at musical curveballs. The Beatles’ once-unified fan base was slow to accept radical facial hair and unconventional clothing; the inscrutable baroque surfaces of these songs harbored peculiar interior fantasies; and the films promoting the two sides of the new single (full of backward motion, color negatives, odd costumes, surreal behavior, and non sequiturs of every order) screamed bizarre by any measure. (Decades later, of course, music videos could take any form a director might imagine, but in the mid- and late 1960s, the Beatles created the pairing of abstract visual imagery to song that, for the first time, did not represent a stage performance.) If Revolver posed riddles, the new single wove deliberately vexing, out-of-reach mystical koans, not least the gaping tonal shift between the ironic cheer of Paul’s “Penny Lane” and the sour sonic hallucination of John’s “Strawberry Fields Forever.” They could have come from two completely different bands. Other puzzles surrounded whatever meanings might lie behind both the four snapshots of toddlers (the band members themselves) on the reverse side of the record’s sleeve and the perplexing monochrome aerial photo of Liverpool’s suburban Penny Lane district used in print ads. (The sleeve’s obverse side appears on this book’s cover. An outtake from the same photo session would be used later in the year on the American release of “Hello Goodbye,” shown as Photo 6.05.) The public scarcely perceived that the Beatles were attempting new poetic expressions of a return to innocence.

We don’t know what led Paul to create a companion piece to John’s new offering, but with the “Strawberry Fields Forever” / “Penny Lane” single, recorded from November 1966 into the following January, we hear two complementary Liverpool odes. McCartney’s Edenic “Penny Lane” has a chipper stride, graced with direct, representational lyrics tracing quaint and quixotic characters who inhabit a clearly drawn picture; the barber, the banker, the fireman, the nurse—habitués of the retail neighborhood in the Penny Lane bus roundabout—all ring familiar. Yet in part because of the way the narrator keeps labeling everything “very strange,” we also engage in a scene full of types, mannequins as stand-ins for lived experience, or the starry-eyed way a child might glamorize the life of a fireman or barber. McCartney’s choice of a piccolo trumpet for the solo (at 1:10) dramatizes this skewed vantage of an “ordinary” street scene. As the high-pitched sound of a “toy” trumpet, evoking an age-old eighteenth-century style, it doubly accents a fading innocence, as the nurse begins to feel that “she’s in a play,” fulfilling the cast’s expectations of her, when “she is anyway.” McCartney had heard this specialized trumpet during a broadcast of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 2 on the BBC and had George Martin notate his hummed melody for the solo.

Lennon’s “Strawberry Fields Forever,” on the other hand, swims in indecipherable, impressionistic imagery vaguely evoking misunderstanding, abandonment, and indifference, all somehow tied to a treasured hallow of trees and fields—a child’s idyll. Paul’s hometown side might be heard as a delightful adaptation of John’s year-old draft for “In My Life,” which originally reminisced about a number of Liverpool landmarks. Although specific references like these did not appear in either “In My Life” or “Penny Lane,” they nevertheless suggested a trip half consummated in John’s Spanish melancholia, dreaming of his youth, contemplating where he came from and how long he had perceived himself as fundamentally different from his peers.

Strawberry Field was a Salvation Army home around the corner from Aunt Mimi’s Mendips. Abandoned by both parents when very young, John identified with the institution’s orphaned children as he attended their annual summer fundraising fair or played in their gardens just a leap over the wall. (The orphanage itself is now long gone, but Yoko’s Strawberry Fields memorial to John lies directly across New York’s Central Park West from their home for his final seven years, the Dakota building on Seventy-Second Street, whose tall carved-stone gables and arched window surrounds echo the now-lost Liverpool edifice.)

Lennon uses an indirect mode to recall his childhood and consider a lifelong otherness to root his fantasy at artistically profound depths. “Nothing is real and nothing to get hung about”; “It’s getting hard to be someone”; “It doesn’t matter much to me”; “That is, you can’t, you know, tune in but it’s all right”: these and other lines express a fluid identity, an insecurity in one’s surroundings, an inability of others to understand him, and a detachment from the everyday in a loose, anti-poetic, conversational style. The lyric speaks directly, without artifice, but resists clarity in fated clouds of obscurity. The song’s complexity and indirectness might be defense mechanisms that filter lifelong negative memories.

Like its lyrics, the song’s musical factors convey a vague and wondrous sense of disassociation. McCartney’s Mellotron introduction articulates flute samples made alien by trimming away their sonic attacks and decays. Lennon’s ambivalent chord choices portray a tonal elusiveness through unprepared pitch alterations and forward- reverse motion in relation to a stable harmonic center. Most pop songs seek and find their tonal home through anticipation and achievement; this one avoids any such center of gravity. Chord connections, such as the unnaturally minor v chord followed by the unnaturally major VI chord, resist clarity in the same obscure posture painted in the song’s lyrics. The same v—VI chord connection will appear in 1968’s “Julia” (first heard at “Julia, ocean child”), at a place where Lennon again filters lifelong memories, joining Oedipal images of his dead mother to those of Yoko Ono, his new lover.

An abrupt jump from guitars and keyboards to cellos and trumpets thwarts any attempt at secure grounding. This transition, which occurs at 1:00 in, famously unites two distinctly different takes of the track: one with guitar band, the other arranged for strings and horns. Lennon had waffled on which version he liked more until he instructed producer George Martin to simply combine the two after the first verse. “I said it was impossible,” Martin replied, knowing that the two takes occupied completely different key areas. “You can fix it then,” Lennon quipped (Martin 1979, 204). Martin’s backroom solution neatly joins these two separate sessions by slowing the first down and speeding the other up just enough to match pitches—only in the “Strawberry Fields Forever” world, each resulting section sounds oddly off-kilter, as if spied through a thick lens, intensifying the overall sense of identity anxiety. Along with the timbre-distorting tape speeds and intermittent backward percussion, the sounds transport the singer and listener deep into the past, to a time preceding exile— or fame. Coming from the most famous pop star in the world, “Strawberry Fields Forever” plumbs irony in how beloved it became, the huge emotional nerve it struck in its boomer audience.

Listeners greeted “Strawberry Fields Forever” with waves of misunderstanding and awe, the composer’s psyche heard center stage but buried under cryptic armor—a habit revisited in “I Am the Walrus,” “Glass Onion,” and “Come Together.” In more recent decades, the song has emerged as a keystone of the Beatles’ artistry and their commitment to human understanding and peaceful transcendence. As fans waited an unprecedented eleven months between Beatle albums, their only clues to what lay ahead seemed both baffling and poetic beyond all previous excursions.