Book Excerpt: What Goes On

Ticket to Ride

Recorded February 15, 1965 for Help!

—the Beatles advance with a new command of simple yet highly contrasting electric guitar stylings that points directly to the creation of hard rock as surely as the song’s details of rhythm and texture do in emphasizing an imposing formal structure. Discussion of pitch, especially chord choices, gets somewhat technical in appreciation of the new year’s complexities.

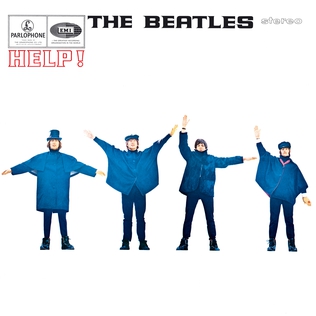

If the underlying structure of the Beatles’ 1965 calendar proceeded unchanged from the year before, great strides in compositional craft, unique instrumentations, and non- rock styles also deserve recognition. Lennon-McCartney lyrics gained new self- awareness: “Help!” particularly peels back its film’s superficial James Bond parody to uncover new depths of personal insecurity; where the movie exaggerates the mop-top image, the soundtrack everywhere belies it. Thus, a curious ironic distance opens between the wacky film spoof and its sometimes sardonic soundtrack. Some general points about the album will be preceded by a detailed look at how instrumental color combines with aspects of melody, harmony, rhythm, and form in the LP’s lead single.

From the opening moments of their first recording of the new year, “Ticket to Ride,” electric guitars gain a new authority; Harrison’s ringing twelve-string launches the song with a powerful line, but the track also features subtle timbral differences and rhythmic vitality from a newly intricate sort of ensemble, partly owing to advantages offered in studio procedures (moving the guitars to their own tape track, thus unlocking them from bass and drums; and overdubbing) unavailable in live performance. The shifts of coloring stem from three new guitars—matching Fender Stratocasters played by both John and George and an Epiphone Casino played by Paul—and a new pedal effect used by George. Ringo’s drumming and tambourine playing combine for tension and release as transforming as that created in the retransitions of “From Me to You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” but in a quieter, more introspective way.

“Ticket” leads off with a bright melodic repeated riff from George’s electric twelve-string. It’s mostly a syncopated arpeggiation of the tonic triad, with one important exception: a dissonant ninth on an offbeat (B against the tonic root, A, articulated on the second half of beat 3) stubbornly pulls away from the first scale degree and leaps up to the chord’s fifth, repeating the riff without a direct resolution of the non-triadic tone, to sneering effect. (The B neither returns immediately to stable root A nor passes to chordal third, C♯.) The ninth escapes the tonic triad, an appropriate emblem of the woman who jilts the singer, leaving him to lament his ex’s newfound freedom. After a tom-tom flurry reminiscent of the “She Loves You” opening, John and Paul enter (0:03) with a growling Strat that doubles the bass on droning chord roots. Although the two repeat a long-unchanging pitch (tonic A supporting the I chord for two bars and then six more once John’s vocal begins, finally moving to B for ii at 0:18 and to E for V, 0:21), John and Paul syncopate their attacks by following each strong downbeat with an accent on the second half of the second beat, and repeating this pattern through the entire verse. Through the six bars of tonic, no one plays a chord—just a drone that also colors the Help! outtake “If You’ve Got Troubles,” pointing the way to unchanging drones throughout much of Revolver, culminating in the mystical bass and tamboura of “Tomorrow Never Knows.” The full texture of the “Ticket” verse’s ostinato—everything played in the recording of the basic track plus an overdubbed tambourine—is represented in Table 5.01, with x’s marking the articulations on every half beat in the two guitars, bass, and drums.

The Beatles’ embrace of non-Western sounds normally gets traced to the late- 1965 use of sitar, but Paul returned from a ten-day holiday in Tunisia on February 14 and, in recording “Ticket to Ride” the next day, asked Ringo to emulate an Arabian drum pattern he’d heard there. This syncopated part is displayed in three strata, one line per drum, in the table’s illustration of the ostinato; x’s indicate hits on the various skins, with “xx” showing the flams that accent off beats through the second half of every bar. Note how the drums’ composite rhythm is fully matched by George’s Rickenbacker part—suggesting that if Ringo were following Paul’s direction for rhythm, George must have created his signature line around the drumming. (Is this how the twelve-string/drums riff of “What You’re Doing” had been put together a few months earlier?) Thus, the “Ticket” ostinato represents a subtle mix of blending and contrast, John and Paul paired against a united Ringo and George.

The verse’s refrain at 0:23 (repeating the song title) itself opens with a harmonic escape, a deceptive vi (following the previous ii–V) prolonged through two different chords that underline the word “ride”: IV7 and ♭VIIM7. The first of these (at 0:25) sets up a bluesy cross-relation between the major scale’s third scale degree, 3 (fifth of the vi chord), and the minor pentatonic’s ♭3 (seventh of IV7), a favorite contrast of Lennon’s as heard in “From Me to You” (1963), “Glass Onion” (1968), and “Cold Turkey” (1969). Tension peaks when vi returns to V at 0:32, at which point John sings a blue ♭7 against his own guitar’s leading tone, 7, at the final “ride.” But before we get there, the song’s newly invented chord, the ♭VIIM7 (strummed at 0:28), takes the ride to such an unexpected destination, the always-moving rhythm stops dead with a cymbal crash for John’s “ri-hi-hide” vocal melisma on three pitches that are not part of the triad, scale degrees 6–5–3 over the ♭VII chord (spelled ♭7–2–4).6 But just as he had added overdubbed color to the first verse’s turnaround in “If I Fell,” George superimposes another version of the ♭VIIM7 “Ticket” chord on his own Stratocaster, in a higher hand position whose voicing places the second scale degree on top, a recollection of the ostinato’s non-resolving ninth, with a stunning, shimmering new pedal effect. The volume-tone control pedal (which George had first heard as used by Liverpool’s Colin Manley in the Remo Four’s mid-1963 B-side “On the Horizon”), removes a sound’s attack and decay and creates a silvery tone like that of a bowed violin; it is also featured melodically throughout “Yes It Is” and “I Need You,” both recorded along with “Ticket” on February 15–16. In this one chord, the confusing clashes of dissonant scale degrees over a chromatic root, the stop-time rhythmic interruption, and the otherworldly guitar timbre combine to show just how far the singer is thrown off his moorings by his loss.

An appreciation of “Ticket” is not complete without reference to two other important guitar effects, plus Ringo’s own superimposition, all boosting the overall ensemble. John contributes one factor in the basic track, in the retransition from bridges to returning verses. Here (at 1:25–1:26), he chugs away with repeated downstrokes on the Strat’s tense V chord, but without thirds, recreating the power chords with which he had built the retransition on V in “I Want to Hold Your Hand” sixteen months earlier. Ray Davies of the Kinks and Pete Townshend of the Who greatly amplify power chords in songs like “You Really Got Me” (1964) and “My Generation” (1965), respectively, but in “Ticket,” Lennon’s sonority resounds more subtly, covered by more attention-grabbing parts, just as in the retransition’s climax in “Day Tripper,” recorded eight months later.

At this point in the “Ticket” retransition, a highly charged overdub grabs our attention: Paul injects a note-bending minor-pentatonic blues lick from his new Epiphone Casino, a hot guitar often verging on feedback that he’d heard played in London’s blues clubs. (This so impressed John and George that they order two matching Casinos; John’s becomes his favorite electric for later work.) At this point, Ringo and George drop out while John’s rock-hard open fifths contrast Paul’s molten melody with impossible flash. Although Ringo does not play for most of this key passage, his crash cymbal lingers over John’s and Paul’s entrances, and the song’s form returns at 1:25 with his alarming overdubbed tambourine rattle and face- slapping rapid-fire subdivisions into eight snare hits. (Enunciating structure, Ringo hits the tambourine on backbeats through the verse, and then shakes it loosely, four to the beat, in the bridge.)

With ‘Ticket,” the Beatles played hard rock months before the Stones created “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” These intertwining elements forge a key step in the birth of rock out of rock ’n’ roll.