Sample Chapter:

Rick James

Rick James Parties all the Time

Boston Phoenix, September 16, 1988

This Boston Phoenix piece ran in the fall of 1988 with the title Rick James at 36 as James toured behind his Wonderful comeback. It was a barometer of how much had changed since his earlier days, with both Prince cementing his stardom and Terence Trent D’Arby a brash new crossover contender. James would have turned 75 on February 1st; he died in 2004.

RICK JAMES SEEMS like a perfect case of a performer who peaked too soon. About 10 years ago he threw together James Brown with freakout guitars and George Clinton with low-minded rationality and called it “punk funk.” It was a fusion whose time had about come, but not enough people were convinced (or not enough after the one big hit, “Super Freak”) that James was the man to bring it off. Sure enough, Prince came along and stole James’ commercial spotlight, some clothes and moves and funk appeal (but not his cornrow locks), and left him beached on the shores of semi-legend-dom, a lightweight but not undeserving funkaholic trapped in the paternalistics indifference of Berry Gordy’s latter-day Motown. James did what any self-respecting self-sufficient careerist would do: waited for his contract to expire, went for the comeback, and began to test his act out in clubs, as his first single in two years, “Loosey’s Rap,” hit the number-one slot on Billboard’s black charts (as usual, white fans, for the most part, are not listening as closely to James).

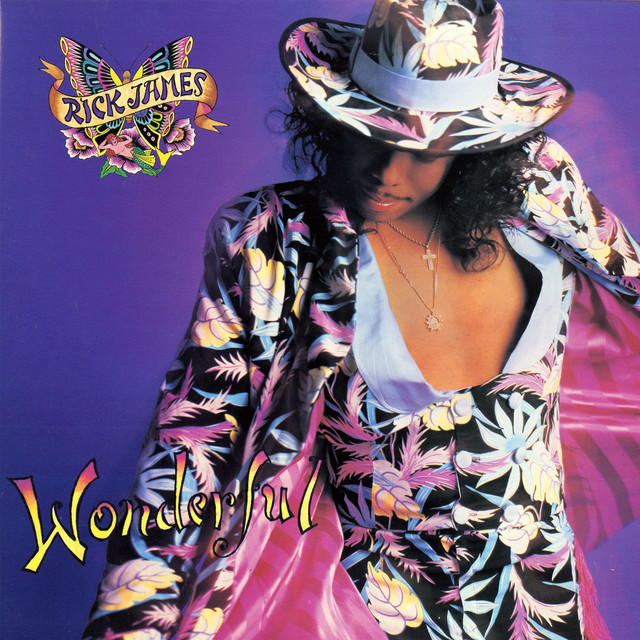

Not that James has been idle. Since he stopped touring five years ago, he’s played Svengali to the Mary Jane Girls, collaborated with Smokey Robinson (“Ebony Eyes”) and Eddie Murphy (“Party All the Time”), produced records for Process and the Doo-Rags and Val Young, and fiddled about at his home studio in Buffalo while shopping for a new label. There were rumors of drug and alcohol abuse and general life crisis, a stint in a dry-out tank. But the period also produced more than 24 new numbers, which got winnowed down to 10 for his debut on Warner Bros. Wonderful. The record traverses familiar James terrain—lotsa songs about sex, simpleminded grooves that get stretched beyond their limitations, all self-produced with the same one-man-band intensity. But James played it safe on the first of two nights at the sauna that was the Channel last week, with songs from his sharpest Motown LP (1981’s Street Songs) and assorted tunes like “17” and “Mary Jane” that positioned him more as a returning hitmeister than as a born-again songwriter. Like the Jacksons’ Victory Tour, which eschewed all songs from the album of the same name, James was out to prove his longevity more than to hawk his new product.

Wearing matching skin-tight Adidas sweatsuits and James’ trademark long curls, his band set out to funk an already perspiration-doused (and fully integrated) oversold crowd that was so hyper stoked for the Rick James experience it began chanting “We want Rick” to house music by Eric B. and Rakim a good 20 minutes before the man took the stage. When he did, to the bump and social grind of “Ghetto Life,” the combined heat from the band and the audience was inspirational—James seemed to sweat for all of us. Jumping up onto Limo Reyes’ drum cage and leaping off, to the delight of the crowd, he made the most of what little mobility was available on stage. With this audience so glued to him, James could do no wrong, though as music goes there wasn’t a whole lot to get excited about.

Perhaps because he’s primarily a bassist, James excels at the mid-tempo groove that draws strength from exertion rather than velocity. Unfortunately, his facility almost always overwhelms his inspiration, making for any number of sound-alike funk essays. “Sweet and Sexy” and “Standing on the Top” are virtually interchangeable, exercise machines that don’t extend the meanings of dancing or sex into more than self-referential odes. James bellows more than either Terrence Trent D’Arby or Prince, which means he hits on the one with more gut urgency than curly falsetto, but his vigor in medium-tempo grunge gets him into trouble in ballads, which sag the longer they spin themselves out.

Like the Jacksons’ Victory Tour, which eschewed all songs from the album of the same name, James was out to prove his longevity more than to hawk his new product.

Make no mistake, James is plenty sincere, but he’s also hardly introspective about his abilities the centerpiece of his Channel show was a three-ballad set (“Deja Vu,” “Happy,” and “Fire and Desire”) that lasted nearly half an hour, with each successive ending more deliberate than the previous—his faked and re-faked ecstasies had you checking your watch to make sure time had advanced. The surrounding songs feature more-sure-footed rhythms, with some sharp horn playing (from Michael Nally, Raymond Greene, and Lamorris Payne) and eel-like synthesizer work by Richard Jayner and Gregory Treadwell, but the slow material in between slumped into mawk. He just doesn’t grasp the mechanics of romantic singing enough for slow ones.

James’ mock-supremacy bit in his songs is equaled only by his annoying tendency to let his female compatriots go uncredited even on duets: rapper Roxanne Shanté gets mention only at the end of a long thank you list on Wonderful’s inner sleeve, though she’s central to what the song is all about. Still, before he plowed into his trio of ballads, James invited Patty Curry onstage for two Mary Jane Girls numbers (“All Night Long” and “My House”), and the show ended with his two randiest (and rhythmically varied) slices of macho devotion: “Give It to Me Baby” and “Super Freak,” igniting the crowd with a showman’s exacting se nse of what it had been waiting for. To finish, he turned, predictably, to Wonderful for “Loosey’s Rap,” which brought Shante out for the role-reversal duet: male supplicant-gossiper introducing female power broker. She shared his stage with the same guileless mode he recruited her for, and that makes the single more than just a fluke rebound on the airwaves.

“Loosey’s Rap” at least creates a dialogue out of James’ sexism, an improvement by any standards. He exalts Loosey’s looseness, and Shante replies affirmative: “I am what I am and I do what I do.” She casually upstages James as an independent black temptress: “I please you because I choose to, and it may or may not have anything to do with how I feel about you,” she seems to be saying, and the most intriguing thing about it is that James still doesn’t care. Finally, it gets Shante out of a contradiction with the don’t-muck-with-me persona she immortalized on “The Real Roxanne.” Sly, curt, and steamy, with clipped electric-guitar riffs darting in and out of spacious bass pathways, the single proves that James can be thoughtful—even somewhat gracious—when he wants to.

Larger arenas are being scheduled for James in October. In a year of Big Comebacks, he has the left-handed advantage of not having nearly as much to live up to as Brian Wilson or Patti Smith. And lucky for him, his already converted audience is simply glad to see him again.