Sample Chapter: Throwing Muses

Rebounding With Hooks

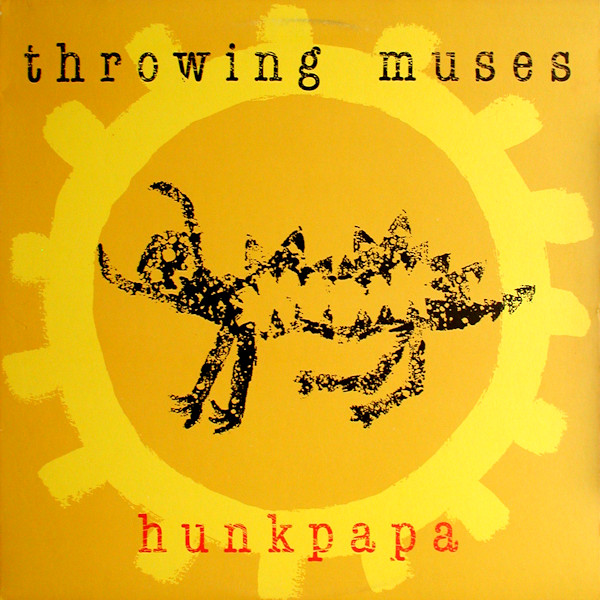

Hunkpapa, Throwing Muses

Boston Phoenix, March 17, 1989

A MOTHER AT 19, Kristin Hersh writes songs for Throwing Muses in the shorthand of someone forced to grow up fast. In her lyrics she yearns for the remainder of an adolescence cut short and for an adulthood that makes sense of working in a rock band. Her elusive song puzzles, spiked by Throwing Muses’ folk punk, can speak to you long before you understand what she‘s on about. Besides the words, the chief difficulty is the songs’ odd shapes.

“Hate My Way,” the fear-inducing number about the encroaching awareness of evil and the centerpiece of the band‘s 1986 debut, leaps from declamatory lurch to swelling ostinato as Hersh‘s stringent whine slaps against thinly arpeggiated guitars, Leslie Langston‘s sinuous bass, and David Narcizo‘s brittle snare shots. Their unmistakeable (if half-aloof) sound made the Newport quartet cult figures in England (where cult label 4AD first signed them). But since switching to Sire in 1986, the Muses have played hard to get with their audience, growing increasingly recondite. Last year‘s galumphing House Tornado was anything but user friendly, indefensible even to longtime supporters of the band‘s rickrack smarts.

On the new Hunkpapa, the Muses have refined their jigsaw ensemble work—abrupt tempo changes, Narcizo‘s brickbat drumming—to the point that even the most lopsided beats begin to make sense. “I don‘t speak I ramble,” Hersh confesses in “Bea,” a disturbing account of a muddied impregnation, love as dirty but free, mother as unsoliciting hooker (“Making babies in the field/Makes me older”). The music here doesn‘t ramble so much as coalesce in discrete, fragmented movements. Hunkpapa is a rebound record loaded with hooks, and damned if it doesn‘t make House Tornado sound plausible in retrospect, a stray blip in a larger wave form.

Hersh‘s bleating simmers down to a lithe wail, like a blonde Yoko Ono with more expressive ability, and her twilight-zone observations (“Nothing makes me older but the birthmark on your back”) meander in and about the time-warp arrangements and pique your attention just often enough to convince you she‘s answering questions you didn‘t know you were asking. The Muses frolic along the edges of asymmetry—if things were any more imbalanced, the center would slide out of sight.

Her elusive song puzzles, spiked by Throwing Muses’ folk punk, can speak to you long before you understand what she’s on about.

Hersh has chased similar obsessions through three and a half records (1987‘s The Fat Skier elongates “Soul Soldier” from the debut). But her motherhood traumas, bleeding self-examinations, and open conversations with fans are sharper here. And producer Gary Smith has made the band‘s familiar electric-acoustic guitar matrix less mannered, tougher (the Sugarcubes should listen in).

In “Fall Down,” Hersh helps an old woman up from a slip in a grocery store and tells her, “Everybody falls down.” Later in the tune, after she shares scars and ambitions with a young fan, the girl says she “thinks she‘ll start a rock band too.” Hersh replies: “I hope you fall so fast and hard that you get me,” suggesting she doesn‘t quite get herself yet, and that falling is the ongoing condition of self-discovery (as it is in “No Parachute”). “Dizzy” is so chipper it could be a parody of bubblegum pop if it weren‘t about a tryst with a Comanche in Oklahoma (“White on red, melt with my skin/These two hearts will beat along the walls of our hotel”).

Guitarist and songwriter Donnelly contributes two tracks: “Dragonhead,” a lullaby that suggests Hersh‘s sisterly alter ego, and “Angel,” which dreads the same procreative demons Hersh has grappled with before and after the fact. Two rickety rockabilly turns showcase the band‘s bony precision: “I‘m Alive” crosses TV consumerism with images of menstruation; “The Burrow” injects cool vocal triads amid two pert verses (with only a single word change) of water-induced drunkenness. Only “Mania,” a hallucinatory squabble, and the closing “Take,” which adds spare horns, come off as indigestible nonentities. The surrounding riddles on Hunkpapa (talk about a wish-fantasy title) float Hersh‘s oblique mother/band-hood perplexities atop sonorities the rest of us can call pop with a straight face.