Sample Chapter: Bob Dylan’s Chronicles

This World Was Lucky

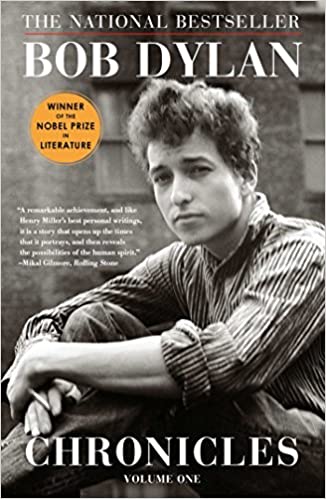

Chronicles: Volume I, Bob Dylan

World Literature Today, September 1, 2005

Dylan invests his original material with so much mythical baggage—what his listeners project onto him and his own cockeyed swagger—that even people who don’t like his voice tend to admit he cuts the definitive versions of his songs. He burrows into his constantly shifting narrative voice with mercurial emotions, bending words to do his emotional will, often turning throwaways (“You just kind of wasted my precious time”) into daggers that go right on twisting (in “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”). And he keeps challenging a legion of followers by tweaking those emotional edges ever so slightly from night to night. Paradoxically (again), playing his recordings over and over has a similar effect.

Separating his persona from his highly idiosyncratic interpretations helps unravel Dylan’s persona. Decoding his renditions of other people’s songs—and written reminiscences about other performers—yields even more revelations. Only when he steps outside his carefully woven facade does Dylan drop his guard to reveal something unexpected, if only for a moment. He did this tentatively on his debut (with his “Song to Woody”) but after that only intermittently. Evaluating somebody else’s song by singing it, or considering the impact of his early heroes, he glimpses the larger show he participates in with something approaching awe. The grand musical narratives with which he identifies (like rock or folk or country) can stop Dylan in midair: time slows, the crowd gasps, and his safety net disappears.

When Dylan made his debut in 1962, he aligned himself with his chief mentor before severing all ties. Long before singer-songwriters had to carry the cross of “the new Dylan,” people were calling Dylan “the new Guthrie,” and it was Woody Guthrie whom Dylan emulated above all others (Hank Williams, Chicago’s Big Joe Williams, Buddy Holly, Johnny Cash, Ricky Nelson). Reading Guthrie’s Bound for Glory in Minneapolis in 1960, where he was busy avoiding classes at the University of Minnesota, Dylan was smitten by more than just this diminutive Okie’s wild-eyed prose and plain-stroke songwriting. Like a lot of other people, he was seized by Guthrie’s vision of America and his life as a troubadour for a culture in search of a voice; Guthrie spoke for his listeners as much as to them. It’s hard to figure what Dylan identified with most: Guthrie’s audience, the hordes of displaced Dust Bowl Okies who descended on California for work, which was anything but a minority; his messianic political ideas redeemed by comic digression; or that Guthrie created a myth for himself that enveloped his vast coast-to-coast existence, an appetite for constant traveling, bumming, and singing that didn’t begin to exhaust what the country had to show him.

One day in 1961, Dylan hit the road from Minneapolis to Morris Plains, New Jersey, to pay Woody a visit at the Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital, where Guthrie lay dying of Huntington’s disease. Within a matter of weeks they were on friendly terms. “I know Woody,” Dylan wrote home, “Woody likes me—he tells me to sing for him—he’s the greatest holiest godliest one in the world.” During Sunday afternoons at the home of Bob and Sidsel Gleason in East Orange, Dylan exchanged songs with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Pete Seeger, and young Arlo Guthrie. As Joe Klein wrote in his superb biography, Woody Guthrie: A Life: “When it came time for Dylan to make his New York debut at Gerdes’ Folk City, Sid Gleason gave him one of Woody’s suits to wear for the occasion. It was an investiture whose symbolism was lost on no one.”

Guthrie was prolific: he wrote at least a thousand songs. But Guthrie passed on more mystique to Dylan than music. To Guthrie, being a songwriter really meant being a song collector. Sharing these songs, Dylan learned how an overlapping persona can develop between a song and the way it’s delivered, between the message and the messenger.

Before the phonograph was a staple of the American home, Guthrie was a roving human channel of an ongoing and largely unwritten oral culture. In the late 1930s, with his singing partner Lefty Lou (Maxine Crissman), Guthrie held forth nightly with his “Cornpone Philosophy” on a two-hour radio broadcast on the Los Angeles station KFVD. The show’s signal reached as far as Pampa, Texas; listeners sent in a thousand fan letters a month.

“I know Woody,” Dylan wrote home, “Woody likes me—he tells me to sing for him—he’s the greatest holiest godliest one in the world.”

Guthrie knew more than a little about how to get along: folks couldn’t go home and put on his records after he sang for them, so he needed to make as simple and direct an impression as he could. Until he became a radio phenomenon in California, many of his fellow travelers heard him once and never again. His on-air musical personality fused familiar melodies and stories, and connected them up to social patterns in novel ways. His songs are repetitious as a matter of strategy: a single hearing lodges them deeply in the mind.

Some twenty years later, most of the personalities on live radio were spinning vinyl. Up in Hibbing, Minnesota, Dylan would tune his family’s Zenith to such scratchy faraway signals as KTHS in Little Rock, Arkansas. Like a lot of other radio hounds, Dylan grasped how repeated listenings gave up different moods, different meanings, and cast light off a song in different directions. Weaned on early rock’s sense of experimentation and incivility, Dylan’s developing taste in music centered on songs that pivoted off innuendo and suggestion in ways that Guthrie couldn’t afford. Guthrie channeled a sprawling songbook by singing the tradition across the airwaves; Dylan retranslated it from there, twisting and bending it back into newfangled song forms: mock epics (“Maggie’s Farm”), circuitous ballads (“Visions of Johanna”), resentful ballads (“Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”), and tall tales (“Highway 61”). His “Song to Woody,” from his 1962 debut, reframes Guthrie’s “1913 Massacre” story-song as sentimental homage.

By 1968, of course, his early burst of talent must have seemed gigantic; his mystique became all-consuming. A triple crown of albums (Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde) cemented his reputation as an untouchable rock mystic. An eighteen-month absence from performing put the rumor mill into overdrive. Was he dead, or would he come back in a blaze of glory to continue his mission? Given that context, Dylan came out of hiding with some very mysterious stories: at the Guthrie memorial concert at Carnegie Hall on January 20, 1968—his first appearance since his 1966 motorcycle accident—the Band backed him on three Guthrie songs: “I Ain’t Got No Home” epitomized the outsider ethos that fueled Dylan’s rock stature; “Grand Coulee Dam” the type of list song Dylan updated with absurdist streaks. The only component missing from this set was political protest: as roundly stirring as “Dear Mrs. Roosevelt” remained, it’s one of the few numbers that tacitly absolved Roosevelt of what Guthrie felt were capitalist war crimes.

Remember the ominous context: Dylan’s return to the stage launched a year that would see the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. and the Chicago riots at the Democratic National Convention. The enormous audience who had invested so much in Dylan’s first act were eager for his second to guide them through the coming upheavals. Instead, he gave them a history lesson.

Guthrie, and his Old Left crowd, had a checkered relationship with Roosevelt. The New Deal was all well and good, but communism was the party protecting workers’ rights in the San Joaquin Valley. Guthrie painted a message on his guitar—”This machine kills fascists”—and nicknamed John Steinbeck’s novel “The Rapes of Graft.” He was passionate to the point of neuroticism about communism (he once argued to his wife that in Russia “the state does the babysitting”).

Guthrie was a sometimes partner in a cooperative musical troupe modeled after the Group Theatre called the Almanac Singers, which formed around Pete Seeger and Lee Hays (soon to be the Weavers), Lead Belly, Burl Ives, Sonny Terry, Richard Dyer-Bennet, and others. In 1940 Pete Seeger began hanging out with Lee Hays and Millard Lampell in a midtown Manhattan loft, an early version of the 1950s beat and 1960s bohemian scenes, a rough model for the Weavers, and, later on, Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue of 1975–76.

Here, his Guthrie tribute glanced at politics only through scathing omission.

Soon after the Almanacs formed, Guthrie traveled to Portland, ostensibly to work on a film, where he got work from the Bonneville Power Administration director Paul J. Raver. For $266.66 per month, Guthrie sat down and wrote some of the greatest tributes to the natural flow of water ever penned, including “Roll On, Columbia” (a sped-up rewrite of his friend Lead Belly’s “Goodnight Irene”) and “Grand Coulee Dam” (to the tune of “Wabash Cannonball”). The latter included the kind of inebriated flow of detail that Dylan would contort into free-form absurdities:

In the misty crystal glitter of that wild and windward spray,

Men have fought the pounding waters and met a watery grave.

Well, she tore their boats to splinters, but she gave men dreams to dream

Of the day the Coulee Dam would cross that wild and wasted stream.

Details like this—the names of tributaries, the localities, the personification of natural phenomena—hooked listeners in. (That “Grand Coulee Dam” image, of course, pops up in Dylan’s “Idiot Wind.”) In Guthrie’s songs, government projects held at least the hope of what an American socialism might mean if it could put its people to work harnessing nature’s magnificence. In this period, Guthrie also wrote “Jackhammer John,” “Dirty Overalls,” “Hard Travelin’,” and one of his best-known titles, “Pastures of Plenty” (“We come with the dust and we go with the wind…”), as well as “Great Historical Bum” or “Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done,” which Dylan evokes in “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” (Klein 194–95). Guthrie joined the Almanacs for a tour that summer of 1940, singing the union and anti-administration songs with charming aplomb, and then returned to rambling.

Later, when Roosevelt ran for a fourth term, Guthrie reformed a few of the Almanacs for a “Roosevelt Bandwagon,” which toured the Northeast during the 1944 campaign. Guthrie sang “The Girl with the Roosevelt Button,” and, along with Cisco Houston, actor Will Geer, and some jazz players and dancers, the show won wild applause in Chicago Stadium, where Woody signed copies of Bound for Glory.

Despite their differences, Roosevelt’s death jiggled a stirring patriotic hymn out of Guthrie. He seems to have concluded that Roosevelt’s good outweighed his bad and that his myth inspired even those who disagreed with his foreign policies. His tribute, “Dear Mrs. Roosevelt,” does more than memorialize the grand wizard of the New Deal while posing as a comfort to Eleanor. In its frank Guthrie simplicity, where inviolable truth poses as understatement, it celebrates Roosevelt’s myth and catches the outpouring of grief that followed his sudden heart attack:

He took his office on a crippled leg

He said to one and all:

“You money-changin’ racket boys

Have sure ’nuff got to fall”

This world was lucky to see him born…

He helped to build my union hall,

He learned me how to talk

I could see he was a cripple

But he learned my soul to walk

This world was lucky to see him born…

Those words shoot through Guthrie’s childlike awe that the man ruled from a wheelchair. They reach toward the widespread identification with Roosevelt’s tenacity from all kinds of displaced folks who weathered a depression and a dust bowl by drawing on more strength and endurance than they thought they had.

That Dylan picks this song to sing in 1968—with his hidden Basement Tapes agenda of “Tears of Rage,” “Too Much of Nothing,” and “Nothing Was Delivered” written and recorded but not released—makes for a strange sense of bygone heroes: even giants like Roosevelt had their Davids, their intimate enemies, like Guthrie. When Dylan sang the swelling refrain, “This world was lucky to see him born,” he commented slyly on how the stature of presidents had fallen during times that seemed no less trying. Instead of critiquing the deceitful war and cynical politics of Lyndon Johnson, or the first Madison Avenue presidential campaign and Richard Nixon’s election later that fall, Dylan sang about how lucky everybody was—Roosevelt, Dylan, folk music itself—to see Woody Guthrie born. In his own songs, Dylan avoided sentimentality as old school. Here, his Guthrie tribute glanced at politics only through scathing omission.

Now that Dylan has actually published some memoirs, suddenly there are a lot more dots to connect. The rambling charm of Chronicles: Volume One (2004), eludes linear narrative as successfully as any Dylan song. If Dylan singing Guthrie tells us more about Dylan the man than his own songs, Dylan’s prose reveals his debt to recorded history and bohemian thought. While it took him almost thirty-five years to put out his autobiography, the words he chooses to describe other singers and performers provides another camera angle on Dylan the Person.

Perhaps he’s poker-faced the rock scene to death, feels that the circus has passed him by and caught up with him again one too many times, and following through on a book contract counts as his least likely move—another triumph that quashed and reanimated expectations all over again.

Dylan’s third act saw its share of comebacks (1983’s Infidels, which pretended his three previous gospel records hadn’t happened), slow-burn descents into mediocrity (mind-numbing forays like 1988’s Dylan & the Dead and 1988Down in the Groove), and sudden reversals (a Grammy for the prettified but turgid Time out of Mind in 1997, followed by the rakishly poetic Love and Theft in 2001). For long stretches, Dylan’s sheer showmanship made you believe he had surpassed Woody Guthrie, that his songs redefined art, that every gesture hinted at greatness. Even when he fell behind on his aesthetic rent, Dylan raised complicated questions. Many thought his long-rumored memoirs were simply another hoax.

At first, Dylan seems to be leaping around without purpose, lighting on particular episodes that seem exemplary only in the slightest sense: conveying a mood or an emotion that’s private and unknowable, and therefore not very revealing (“The moon was rising behind the Chrysler Building, it was late in the day, street lighting coming on, the low rumble of heavy cars inching along the narrow streets below—sleet tapping against the office window…”). But when he returns to the Village, Dylan recaptures an innocence his music has long since lost. Reading this book you’d never recognize Dylan the Icon who appears onstage at The Concert for Bangladesh in 1971 (one of his four or five great live sets, unmentioned here), or Dylan the Zombie, surrounded by Neil Young, Roger McGuinn, Tom Petty, George Harrison, Booker T. and the M.G.’s, Rosanne Cash, and others at his own 30th Anniversary bash in 1992 (also unmentioned). Those career markers seem as immaterial to him as his 1988 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame or his 1991 Lifetime Achievement Grammy.

To learn what Dylan really cares about, turn to where he articulates his carny’s grasp of hokum and infamy. When his ears prick up to other singers, Dylan’s descriptions soar, like his portrayals of Ricky Nelson or Johnny Cash or Hank Williams. Here’s Dylan on Roy Orbison:

Orbison, though, transcended all the genres—folk, country, rock and roll or just about anything…With Roy, you didn’t know if you were listening to mariachi or opera. He kept you on your toes. With him, it was all about fat and blood. He sounded like he was singing from an Olympian mountaintop and he meant business…He was now singing his compositions in three or four octaves that made you want to drive your car over a cliff. He sang like a professional criminal.

Compare that passage to this, at Johnny Cash’s house with Graham Nash, Kris Kristofferson, and some others, trading tunes, when an anti-Semitic remark from country music patriarch Joe Carter stops the camaraderie cold:

I played ‘Lay, Lady, Lay,’ and then I passed the guitar to Graham Nash, anticipating some kind of response. I didn’t have to wait long. “You don’t eat pork, do you?” Joe Carter asked. That was his comment. I waited for a second before replying. “Uh, no sir, I don’t,” I said back. Kristofferson almost swallowed his fork. Joe asked, “Why not?” It’s then that I remembered what Malcolm X had said. “Well, sir, it’s kind of a personal thing. I don’t eat that stuff, no. I don’t eat something that’s one third rat, one third cat and one third dog. It just doesn’t taste right.” There was an awkward momentary silence that you could have cut with one of the knives off the dinner table. Johnny Cash then almost doubled over. Kristofferson just shook his head. Joe Carter was quite a character…

“Quite a character”? Are we supposed to think this old-timey Tennessee bigotry didn’t faze rock’s impassive Yoda? That Dylan didn’t blanch at Carter’s slur? Did he simply admire the man’s music too much to be offended by his anti-Semitism? Perhaps. And yet the scene is drawn here with great confidence and ease; the effect is of quiet horror: that “awkward momentary silence” just sits there, out of reach. This queasy restraint is probably as close as Dylan ever got to modesty.

What’s a critic to do? Knock Dylan for turning literary larceny into a best seller? Chronicles should have been longer, but it’s infinitely preferable shorter (my own hunch is that it’s some unsung editor’s triumph of concision and shuffling). Perhaps Dylan is one of those writers who throws a couple hundred bad songs away chasing a decent piece of prose. Perhaps he’s poker-faced the rock scene to death, feels that the circus has passed him by and caught up with him again one too many times, and following through on a book contract counts as his least likely move—another triumph that quashed and reanimated expectations all over again. Perhaps the notebooks he kept started pulling him back in, he found inspiration in writing about other people’s music, and Chronicles poured out of him as if a different medium had suddenly sparked the old muse—like one of those dusty crowd-pleasing flips he stumbled on during a slow night on the high wire. He gives it extra play on a whim and surprises himself yet again with how the words start to sing on the page, how much his imagined sense of the crowd buoys him. Suddenly, catching his balance, he snaps back into the habit of pleasing himself with his innate skill at making the crowd roar. Just for kicks he does it again, then falls down backward into his net, grinning.