Leon Russell Learns How to Boogie

listen to this interview

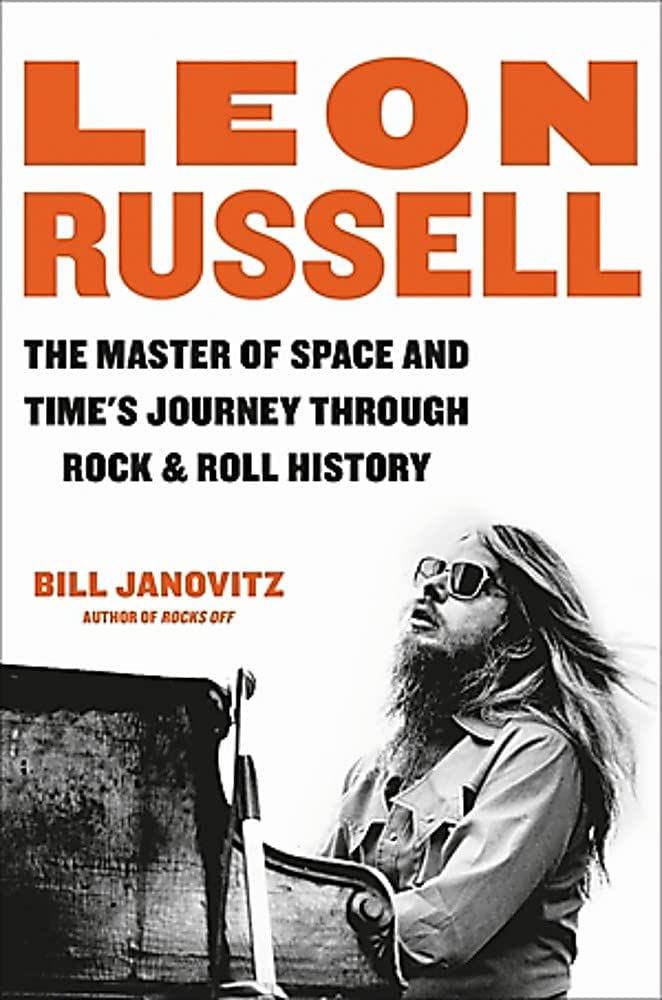

Leon Russell, the Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock’n’Roll History

by Bill Janovitz (Hachette Books)

TR: I love your book. I love love, love the Leon Russell book. I’m so glad you get I get to talk to you. I’m learning so much about Russell. I knew he was a big player backstage but I really just didn’t know the extent of it. And his tentacles reach everywhere, I went and listened to the Helen Reddy song that he wrote you know, I mean just like cool shit like that. But I have a very fond memory of seeing Leon Russell at Folsom Stadium in Boulder, Colorado. I would have been 13 and I (can’t figure out what is said here) this concert and it was the hippiest, dippiest, grooviest thing you know, he was out there to do the Leon Russell live stuff, all that material. He was the grooviest guy alive and there were all these rumors that that gray hair was real, like he’s super old man, he played with Sinatra. I just have very fond memories of that.

Anyway, great stuff. So we know you as, how do you call yourself? Lead singer-songwriter-guitarist for Buffalo Tom? And your Instagram is full of these gnarly Rolling Stone licks, oh my God.

BJ: [laughs] I mean, Buffalo Tom has been playing a lot of those songs for fun for all these years. But yeah, I mean, I am one of the founding three of Buffalo Tom and never really broke up per se and we took long breaks from each other, including through this pandemic, but we’re working on new material now.

TR: Oh really? That’s wild.

BJ: Yeah we’re with Dave Minehan [The Neighborhoods] over at Woolly Mammoth Studio.

TR: I just love how it’s just progressed so far beyond what anybody could possibly think. I mean it was unthinkable, right, in 1988 that we would be here today? And the story plays out in so many interesting ways.

BJ: Yeah, in fact, when you brought up that Rat show, and you said I’m not sure if who else was on the bill, one of the bills we played on in those earlier days might have been that one opening for Soundgarden after Rat, which is crazy to think of, you know.

TR: I remember meeting those guys at the Rat, yeah. They were young, hungry, very ambitious, and really happy to meet a journalist—and not a lot of people were [laughs]. But so, Buffalo Tom. Give us like a capsule career of Buffalo Tom’s origins, first career stretch, and then what you’ve been doing since, and what made you do a book project on Leon Russell? I know you have a couple of books in there.

BJ: Yeah, sure. So the thumbnail is, Buffalo Tom started up at UMass Amherst in late ’86, and we got going pretty fast. I mean, I was still at school, the drummer Tom McGinnis was still at school, and Chris Coburn was just about to graduate I think. And we kind of stuck around the area, you know, dragging out our school career as much as possible, but we tried to SST records home of back then, found Soundgarden, Sonic Youth, and Dinosaur Jr., who were also up at UMass for that matter. And it was actually J. Mascis of Dinosaur Jr. who was kind of a friend of ours whom we had played a little bit of music with parties and stuff, and said would you produce us? He had wanted to kind of start working with other bands a little bit, even back then. So we started at the earliest nascent versions of Fort Apache Studios in the first one, which was in Roxbury. Pretty soon we had Tim O’Heir, Paul Kolderie, and Sean Slade working on your first couple of records and all those guys went on to create things. If there were sort of one unifying element to all of the indie bands coming out of Boston — and by the way, there were tons of them, it was really difficult to play in Boston back then, even though there were way more clubs, there were even more bands — one of the unifying elements between let’s say, you know, Buffalo Tom, Throwing Muses, Lemonheads, Julianna Hatfield, Blake Babies, etcetera, Big Dipper, Volcano Suns, was that we all recorded at Fort Apache, at least a little bit or some of us a lot. Anyway, one thing led to another we were starting to have some overseas labels as well. Soon, Beggars Banquet was still going strong, they signed us and they became basically our label through our whole career, licensing us out to different major labels in the states. And then, you know, Nirvana broke, and as you said, who knew that it would get this far? It was really kind of a stretch and a goal for us to play a T.T. the Bear’s, never mind headline. And I always say, you know, we were headlining in London and Holland before we got a headline engagement in Cambridge…

TR: Yeah, and that was typical for that era. I remember that space really well, like the Pixies were not on a local label were they?

BJ: The Pixies were assigned to Four A.D. which was under Beggars Banquet, one of their imprints basically…They were big in the UK…. Another unifying element through Fort Apache was Gary Smith, who basically took over the management of Fort Apache and took over ownership of it with Billy Bragg and some others. So Gary discovered essentially both Throwing Muses and the Pixies and produced both of them and got them signed both to the Four A.D. label and brought them over. So Throwing Muses were already big over there and then the Pixies were opening up for them, But then the Pixies exploded to the extent that they switched the order of who was headlining on that very tour, so it was an exciting time. I mean, to even part of that whole scene was great, and you know, then Nirvana started to break, which is the biggest example but yeah, also Soundgarden, and Pearl Jam also of Seattle, Dinosaur Jr. from here, Lemonheads… everything started to get bigger. People that were college radio DJs playing us were now real DJs playing us. And so we’re at MTV all sudden and the whole field started to change and things became more of a quote-unquote, career, you know. It was quite a trajectory and we rode that out until the end of the 90s, and then we said “Okay, kids coming, we didn’t strike it gigantic, maybe let’s peel back a little bit and get off of this roller coaster.” That’s the short version, and then I got into writing books and we all did some other things. I wrote a couple of books on the Stones, one of which was for the 33 and 1/13 series, on Exile on Main Street, and then another one for their 50th anniversary, which got a bit more noticed I think.

TR: Great, so talk us a little bit through those two Stones books and then how those lead you to Leon Russell.

BJ: Well, I was really intrigued with the earliest days. I think mine is, one of the first ten books [in that series}, if not less for 33 1/3 back then, my friend Joe Pernice on Meat is Murder and Joyce Linehan who is still his manager, I asked Joyce if they’re looking for other ideas, and she connected me to David Barker, the editor then. I mean, Exile on Main Street has been my favorite rock and roll record all of these years, so I wrote a book on that and I wasn’t planning on doing another Stones book, but, those was like 04, 05; a bunch of years later in about 2012, an agent approached me from the UK and said “Hey, the 50th anniversary is coming up, I have this idea,” and he sort of based it on Revolution in the Head Ian MacDonald’s book about The Beatles, which I don’t know if you’re a huge fan of. And I used that as sort of a template, in other words, taking songs and putting them into the context, weaving the biography of the bands throughout, and kind of analyzing the music as well. So that was the second one and from there, an agent in the States really was into that and we talked (his name’s Peter McGuigan) and from about 2013 until 2019 we were sort of casting around for ideas. I had pitched him an idea of doing something on Mad Dogs and Englishmen, the tour was Joe Cocker that really broke Leon through into public consciousness. He said it was a bit too small maybe for a full book, but I don’t know how many years later, I get an email from him saying “Hey, you passed on Leon Russell,” and I said “I did not pass on Leon Russell!” [laughs] Somebody from the estate of Leon Russell had connected with them and they were looking for an author to write a book on him. So they were very cooperative with me, and I guess sort of authorized, but nobody from there has even read it yet from the estate…

TR: [laughs] That’s the best kind of authorized.

BJ: Exactly, yeah.

TR: So a couple of Stones questions. This may be in one of the books, so apologies, but do you have any clue why “Plundered” was left off of Exile? Because when that came out on the Deluxe version I was like, this is a master hit. I can’t believe it didn’t make the cut.

BJ: Yeah, I discussed this in that book, I don’t know why it was left off aside from why any of their outtakes were left off. I should say it was incomplete. And I just remember I was riding in my car and somebody on BCN, Carter Allen, played it and I was like “What is that? It sounds like the new Stones capturing the old Stones somehow.” Because it’s Mick Jagger’s newer voice. But I just thought what an amazing song. It’s one of my favorite songs. But having learned it, I think I’ve picked up that it’s basically a loop, you know? They found like a short recording of this groove with maybe it’s got that one change, it doesn’t have a bridge or anything else, and I think they just looped it and Mick created a song out of it because if you listen to Charlie’s drums, they’re uncharacteristically kind of the same throughout. He usually varies patterns, so I think it’s like a loop that they found. And I think probably maybe Mick Taylor came in and overdubbed his solos and stuff.

TR: So do you think that they found this fragment and Jagger actually did a new vocal on it?

BJ: Yeah, I mean, if you listen, that’s definitely Mick now and I don’t think there were any vocals on that. Typically, there would have been a guide vocal, and you could often hear Mick, like for example on, probably the loudest version is on Angie, you can really hear Mick’s ghost vocal in the room while they’re recording the basic track while he’s doing the actual lead. But yeah, you could kind of tell it’s Mick’s voice circa 2012. But the song came out as I was almost finishing the book, I haven’t talked to Don Was or anybody about it, but I’d be eager to know the background of it but I think it was just a loop…

TR: Did [Don] Was supervise that Deluxe? I can’t remember…

BJ: Yeah, he was working with them very closely throughout that era, on newer and on that project. I think there’s that video on the project, I haven’t revisited this in a while, so forgive my fogginess, but as far as I recall, he’s sort of the thread in that little mini-documentary that they released with it.

TR: And would they have brought Mick Taylor back in 2012 to do a lead on that track?

BJ: I’m pretty sure, yeah, I’m almost certain that Mick Taylor came in to do some overdubs, unless that stuff existed and they were just jamming, but I’m pretty sure that either way they did bring Taylor back in for some overdubs, By that point, I saw them on that 2013 tour and Mick was showing up at many dates.

TR: Oh, that’s interesting. I’m out of that loop, I didn’t realize that. And he was sitting in?

BJ: Yeah, he was. He was very often on “Midnight Rambler” live, you can see him in all the clips on YouTube. Even later… He might have come for the Fonda Theater to play Sticky Fingers, I’m not sure. They got way better live in the 2000s than they were in the 90s. The live show got much better.

TR: Yeah, I saw them at Sullivan Stadium show I think in ’93. That was terrific. What I remember is that Mapplethorpe was in the air and they did “Sympathy For the Devil” and it was this wonderful convergence of how prophetic that song was. Not only of its time, but still relevant. And I just remember it being a huge space. But it was very clubby on stage and I remember being very impressed with how clubby it was. And then ’93 was sort of more corporate, but I remember thinking, “Well, that’s probably it,” you know? Like we were all thinking, at every phase of the career, right?

I also saw The Who in ’89 at Sullivan Stadium and I thought “Well, I thank God I saw them.” I brought very low expectations, and they really delivered and they were wonderful. But I thought that that was it and 300 years later [laughs]

BJ: They’re kind of back, even though Mick and Keith are the only originals standing.

TR: I’m also really offended about how they did not let Darryl Jones in the group photos… Especially in this era, if you’re going to be answering charges, and discuss race now, which you have to do, but we’re not gonna let Darryl Jones in our photo? Fuck that man, I’m sorry. I just think that it really makes me listen differently. It really does. And I stuck with them after fuckin’ Altamont, Jesus Christ.

BJ: Yeah, it’s interesting, because even though Ron [Wood] wasn’t a full member of the band for a long time, he was always in photos from the get-go, but I think part of the reason they were actually attracted to Darryl Jones was not only his pedigree, but I think they liked the idea of having him.

TR: Right? Like it’s about fucking time, let’s get a Black member on the band. Let’s make him the new core of the band, and lock him in with Charlie, absolutely, it was way overdue. But no official group photos. Man, I think that conveys far more than they realize.

BJ: I hear you…

TR: …the colonialism and just all the old bullshit.I think it’s Churchillian, that’s what it is. So tell me, what else did you learn? You’re obviously much closer to the bone than I am on this material. But what else did you learn from that Deluxe box that fascinated you right after the book came out?

BJ: Well, I don’t, I don’t know, when did it come out, I think I wrote about “Plundered” as the last song of the 50. Having written that 33 1/3 book on it, going back to that, first of all, I never agreed with this idea that it’s just murky mix. I think people have imprecise terms for what they’re trying to say; it’s definitely a murky mood, but the mix of that record always sounded crisp and great to me. I mean, if your mind only goes to something like “Just Want to See His Face” or something, then it’s going to certainly be murky but that’s by design. My job in both of those books, primarily the first one, was to convince people that it’s not only the best Stones record as far as I’m concerned, and that can be argued to death but to me, it just encapsulates almost everything up to that point that was great about rock and roll. It takes the blues, the country, the soul, the gospel, to the Leon book… Yeah, so that’s kind of why I was attracted to Leon and just figured, not knowing that much about him either, I knew the trajectory. Even as a little kid, I have always been attracted to gospel music and gospel via Ray Charles and Sam Cook, and to soul, and Aretha. That stuff has always really floated my boat. And I loved that era of rock and roll that sort of post-[The] Band, post-John Wesley Harding, back-to-the-roots kind of mood where not only had these bands eschewed their psychedelic pretentions to come back to sort of meat-and-potatoes thing, but specifically with the gospel element. And I knew that Leon was fundamental to that because I loved that record, that Mad Dogs and Englishmen record as a 12-13-year-old, but I don’t think I knew how pivotal he was of course, launching off of Aretha and specifically Ray Charles, but bringing that stuff back to rock and roll. So like for the Stones, that’s what I love about Exile as well, how rooted in the gospel it is.

TR: I might get this wrong, but it seems to me like they dwell in the blues and the culture of blues as early as Beggars Banquet, and you know, “Love in Vain” and then they very tentatively sort of approach gospel as the last leg of their stool.

BJ: Yeah it started with “Salt of the Earth,” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” is pretty, yeah… As you said, they didn’t throw themselves fully into it, it’s like they didn’t quite trust themselves. They’re such an uninhibited band, the kind of band that can write something like “Brown Sugar” because of Mick’s audacity, but even back then I think they were a little tentative of dipping too far into it or not knowing exactly how to nail it, because you have more of a juxtaposition. Instead of a gospel choir, you have the London Bach Choir on “Can’t Always Get What You Want.”

TR: I really liked this idea about how detailed the mix of Exile is because I find that blurry take on it too. I mean, the timbre of Charlie’s cymbals being always really important to what he’s doing; it’s not just that he changes his patterns, he’ll just change the position that he’s hitting the cymbals at and it’ll just give them a new flavor. And that’s not like something you hear in a murky mix, right? You have to capture that.

BJ: Correct.

TR: But the other new switchover, or the new accent that they’re really bringing to the fore is Ian Stewar and Nicky Hopkins on Exile are just like primary players. Some of the great licks on that album, especially as you get towards the end, are pianos licks, It is a guitar-dominated record, there’s no way you can say it’s not built around guitar, but there is this really interesting like, it’s like the piano is suddenly a coequal there.

BJ: Yeah, you talk about Beggar’s Banquet, they built “Sympathy for the Devil,” I should say they tore it down because you can see that the making of it in that Godard film, subsequently called “Sympathy,” before it was called One Plus One. But anyway, you see this great gift of them going through this creative process and there is Nicky through the whole thing sort of quietly leading the way into this piano samba thing and it doesn’t even have an electric guitar on it until the solo and that’s the only electric guitar on that recording of “Sympathy.” It’s so driven by the piano…

TR: As was “Let’s Spend the Night Together,”

BJ: Yeah and “We Love You,” I mean, you talk about The Who, Nicky is all over that Who stuff like “Anyway, Anyhow[, Anywere],” and The Kinks, but they knew they knew what they had with Nicky as they did later with Billy Preston, and even Leon Russell playing on some stuff. He plays the second piano on “Live With Me” and on Let It Bleed. But to your point, Nicky is one of the, in a record of highlights, he is one of the great things to listen to and zone in on, like he zooms in and “Rocks Off” and takes it to another level. But, “Loving Cup,” he begins the song solo and it’s just beautiful. One of my favorite parts is what he does on “Ventilator Blues,” it’s just torrid and smoldering, it’s great.

TR: So, and this is something I learned from your book and it’s that Leon plays a second piano on “Live With Me,” tell us that story.

BJ: Yeah, so he went over to do his first record — Leon, and this was right before the Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour — he had been a session guy all these years and he became extremely well known I should say among especially the British rock illuminati for his work with Delaney and Bonnie on the Accept No Substitute record. And I talked to you know, Clapton and Elton John, all these people that turned on to this record and piano playing and hearing somebody do this sort of Gospel style. And so he hooks up with producer Denny Cordell who has produced Procol Harum and Moody Blues and Joe Cocker, and he worked with Joe closely, and Denny takes this guy over to London to work with Glyn Johns at Olympic, and record his first debut record as a solo artist. And the band basically is Clapton, George Harrison, Ringo, Steve Winwood, Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts… I mean, it’s madness, right? Like all these guys had kind of heard about this guy, and Keith and Mick were there for a bit, and they in fact run through an early version of “Shine a Light,” which later appeared on Exile. And you can kind of hear Mick feeling his way through the song and you could hear Leon really steering this gospel style that Nicky picked up on. Nicky had already been doing this stuff, but he really picked up on what Leon was doing there. And so they’re taking the plane back, and at this point, Leon had connected with Chris O’Dell — who has got a wonderful book out called Ms. O’Dell, I could just talk about her for a long time — but anyway she was working at Apple for The Beatles, and she came back as Leon’s new lady friend. So they were flying back to LA and they couldn’t get first class tickets because the first class tickets were all booked up by the Stones and their entourage, so Charlie and Bill came back to coach and said hello in coach, and once they got back to LA, The Stones said “Hey, let’s get Leon on a track or two.” And in fact, Leon arranged the whole horns section for “Live with Me,” that got jettisoned and they left on Bobby Keys’ sax.

TR: So Leon, he could read and write music, but he’s playing with all these people who basically are ear players right?

BJ: Yeah, he was. He was definitely an arranger. He himself, he talked about his session days of being like overestimated, he was humble, but I think he was also being pragmatic. He’s like “I can’t lead complicated stuff,” is basically what he said, but he could arrange. He did these, I think I use the term “gobsmacking riffs,” so if you’ve listened to “Echoes” by Gene Clark or all that goofy Gary Lewis and the Playboys stuff, it’s goofy, but it’s the arrangements are brilliant pop arrangements. But he did Pet Sounds-like arrangements at the same time that Brian Wilson was doing that kind of stuff. But yeah […] he wasn’t a jam guy either, so it’s not like he ever wanted to sit around and jam with people. He was definitely more on the arrangement side of the equation.

TR: And you go into a lot of detail. You talked to everybody, it seems like you’ve got everybody who was close to him or lived with him. His house was sort of like a combination of flop pad and studio. And that his girlfriends report that he was really pretty moody, that in retrospect, he called his mood swings pretty manic. Tell us more about how you learned about that…

BJ: Yeah, it goes back pretty far. Almost everybody that I talked to that knew him closely said, you know, nowadays, we would call this bipolar, we would call it manic depressive a few years back, whatever it is. And it would be… sort of days and days of activity, manic levels of activity and focus, and drive, and then there would be potentially up to maybe a month at a time where he wouldn’t leave his bedroom. He would go into dark periods. But it was mostly internal, like, you never hear anybody talk about like temper, or rage, or anything that would be sort of external responses it was just internal. And he had these demons as a lot of artists do. And you know, without being stereotypical about it, I mean, he did have what would often be considered part of that artist’s temperament. And he did some self-medication. I mean, he wasn’t a bad drug guy for a long period of time. I mean, he did the typical experiment with LSD, which you know, is to be a separate conversation from people that are self-medicating with booze or cocaine or whatever else, heroin, but he did get into Angel Dust, which was quite a strong and destructive drug, you know, Jim Keltner talks about that quite a bit in the book. But yeah, I think it was difficult on his relationships. And then he later I think, my big revelation for the book and what I think will be news to even the die-hardiest of Leon fans was that he considered himself to have autism, to be somewhere on the spectrum, which he kind of figured out later on in life after watching a documentary on the subject.

TR: So what was the hardest part of the book to write for you? What was the biggest challenge?

BJ: The biggest challenge in the whole process was the editing process because — I’m sure you could tell just by this conversation — I’m kind of a long-winded person [laughs]. Yeah. And I mean, it was COVID, it was during the pandemic, so it was kind of a perfect project to do for me. It was also perfect in terms of accessibility because you know, you want to talk to Eric Clapton, he’s home. You want to talk to Elton John? He’s home. Willie, Nelson’s not on the road again [laughs]. You know, these guys wanted to talk about Leon Russell. Rita Coolidge, Claudia Lennear… great opportunities and my great fortune to be able to do that. And they all have amazing stories. It could have just been an oral history, and sometimes it verges towards that. So for me, the challenge was, which of these four stories that Claudia Lennear told me are to be cut? You know, which one sticks? And, I’m not a great editor at all. I’m not a great proofreader. I’m not great at making decisions. So that was the greatest challenge for me, winnowing it down to this gigantic book that I already actually write.

TR: Right. So what is it? I mean, it’s long, but tell me how many pages it is.

BJ: I think it’s 535?

TR: What did [how many did you] you turn in?

BJ: I’d rather not speak of it [laughs]. Yeah, I had a misunderstanding with my editor, who is a saint. I sat down with him to sketch out the book in New York, and he’s like “Don’t worry, you know, we’ll make the choices. Just get me what you’ve got,” and I hand him what I’ve got and he’s like “This is not a book!” [laughs] It was something like over 1100 manuscript pages. But I did not expect that to be the book, I knew it had to be cut a lot, to say the least. Yeah. But I thought he would help me make those choices, but I mean, no human has the time to do so many. So we had another couple of steps before we got down to what we actually worked on.

TR: And whom did you find to be the most surprising interview?

BJ: Eric Clapton. You know, Eric’s become this sort of thorny public character. He was maybe since the 70s let’s say, when he waded into his own racist tirade, drunken or otherwise. And, but, you know, there’s just this social media era of, say, reducing people to these kinds of cartoonish versions of themselves. He does no favors to himself — kind of like Van Morrison — they’re more complicated than their worst moments. And I’m not in any way excusing either of them, but yeah, I went in there with all this prejudice, for lack of a better word, and just preconception of who I thought Eric had become. And I have gone on this whole journey starting at age 12 as a guitar player to now, and I know about who Clapton is as a musician, and I find him a fascinating character for a bunch of reasons, musical and otherwise. But as an interview, he was just fantastic. He was humble, he told me amazingly detailed stories — I think he was a diary keeper — and I was astonished at his memory. We discussed guitars, his singing, how he was the first one to express and acknowledge his influence, the influences like doing records with JJ Cale and Delaney and Bonnie. I mean, he’s just a great music fan, so we had a good long chat, as I did with Jim Keltner and some others. I just thought the whole process was an excuse for me to talk to my record collection, this book. But I would say that Clapton didn’t want to get me off the phone, you know? I had a lot of people who were like “Okay, are we done here?” You know, that’s great. Thank you for your time on the phone, but with Clapton, we could have talked for another hour, I think.

TR: I think it’s very well said, that people are more complicated in their worst moments.

BJ: I would say among guitar players, especially the sort of cheekier, more insolent, guitar players, like myself. For me, who grew up in punk rock and saw virtuosity, I was, in hindsight, threatened by it and pointedly couldn’t achieve it. But when I was coming of age in the late 70s, it was all about Van Halen, and [Jeff] Beck and all these guys and Steve Vai eventually, and first of all I didn’t like that stuff yet. And I didn’t really and I went, Oh, yeah. But, you know, you’ve got to contextualize; there are different discussions to have about Clapton. There’s the guitar player who you don’t understand but it’s like Jeff Beck as well and you don’t understand what they were doing in the late 60s even though they were borrowing heavily from Freddie King or whoever, this was not just revolutionary, it was extremely innovative and [unintelligible]. Now, it’s a whole different thing, and then there’s Clapton as a frontman, which he never really wanted.

TR: That’s the key for me is that this guy plays great on everyone else’s records. He should not be making records. I mean, Slowhand, what a boring fucking record. And he wanted to be J. J. Cale, I mean one J. J. Cale is almost one too many…

BJ: Well, let’s go back to the first Clapton record, which is basically , as I say in the book, it was really finely tuned but it’s Delaney and Bernie, he’s just playing the part of Delaney, but I think that’s fascinating because it is a great record and it is great with Delaney and Bonnie as the band. But then, Layla was for me his absolute peak, such a peak that it’s above everything else. And he never came anywhere close to that again. And then he became, as you said, J.J. Cale, but a less interesting version of J.J. Cale, and there are some good songs in there, but I find it very interesting.

TR: I think that’s the argument. That’s a very good pushback, it’s that it’s really interesting, right? Because here’s this guy with all this facility and all that access and you know, no celebrity and fame and and it’s just freakish, who it happens to, why it happens, so he finds himself like with this graffiti, “Clapton is God,” like what are you supposed to do with that? Finding your way through that and developing a career, yeah I think Layla is freakishly great, but you know the longer he keeps making mediocre records, the more freakishly great it gets. Right?

And how much of that is Duane [Allman], too?

BJ: Duane played a pivotal part on the record, but it was small. It was really Derek and the Dominos, which is the core of Delaney and Bonnie, and you’ve got Carl Radle, Jim Gordon, it’s just incredible, right? Yeah. And, Bobby Whitlock really is responsible for that.

TR: Remind me, what is the Whitlock connection with Russell? I mean, would it make sense to have Russell on that record?

BJ: Leon was already a star by the time Derek and the Dominos came out, well, let’s say he was on his way to becoming a giant star. So he was already concentrating on his own career and they went off on the Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour to do that and his record had just come out, so he had put together a band without them, but Bobby Whitlock was sort of the youngish guy in comparison to all of them. He had come out from Memphis with Delaney and Bonnie after they were recording at Stax, [Booker T and the MGs bassis] “Duck” Dunn had introduced them, so he followed them out to LA and I mean he’s completely unreliable and a little bit all over the place. His books are good he’s been on YouTube with his wife Coco telling stories for the last few years. He’s used to speaking off the cuff and some of it makes no sense, and some of it makes a lot of sense. But yeah, so he was up at Leon’s place a lot during those days and I think he looked up to Leon, but he also takes some credit and says that Leon asked Bobby himself as well as Delaney and Bonnie both of whom had preacher, fire and brimstone preacher fathers, and how does this stuff work, and Leon incorporated the act in the early 70s and it was all about this, as he called it, artificially induced religious experience.

TR: Right, and he’s taking the gospel secular thing to extremes, and my understanding of it was that he just kind of wore it out, you know? Like he got to be a one-trick pony after awhile and he set by 76, right, you didn’t want to go see Leon because you knew that it was just going to be “Jumping Jack Flash” again. I mean, he just got kind of stale. Is that a misimpression?

BJ: Yeah, I mean, there’s a few steps to that. To a fault, he switched horses midstream very fast. Like he first did that “Hank Wilson” country record in 76—

TR: —Which was my first country record and he’s one of the big reasons of that huge country fan.

BJ: But he risked alienating a lot of his fans and I think a lot of them were scratching their head because the next record he puts out is Stop All That Jazz with the Gap Band, which nobody knew. He discovered the Gap Band with some friends in Tulsa, so he does this very weird record, it’s not a very good record though it has great highlights. If you know the version of “The Ballad of Hollis Brown” on there, it is insanely great. It’s like a pounding, pre-industrial, almost like a suicide, Georgio Morodor meets a chain gang version of a Dylan song, it’s a great [unintelligible] of that murder ballad. But then he goes and does this comeback record called Will O’ the Wisp which is a really good record and that’s when he sort of met Mary his wife, but then he basically just shoots himself in the foot. He ruins his relationship with Denny Cordell and he does these two duet records with Mary that are completely different from anything he’s done. They’re basically aimed at the AM top 40 of the 70s, which are lovey-dovey song. No kick-ass gospel piano at all on that or very little, I should say.

TR: So tell me more about the country record he did, Volume II a few years later…?

BJ: So it was a long time coming. I think Volume II comes out in the 80s and there was a third version that came out in the 90s. By the time the third one came out, it was a real breath of fresh air because he had been in one-man-band self-released CDs territory and you know, it’s really hard to find anything to like on what his stalwart bass player called “the merch records,” you would have tables of [laughter, unintelligible…]

TR: Interesting, so talk any more about Mark Benno, because another phase of the Russell crew I really love is the Asylum Choir stuff. So what are there, two records? Three records? What happened to Mark Benno and what created that duo?

BJ: Yeah, so these are the original Leon as an artist records because everything else he had been doing was sideman and arrangement stuff. …Leon was [Liberty Records’s Tommy] “Snuff” Garrett’s right-hand man, he was his producer basically, the arranger. So “Snuff”was like an old-school record guy and they formed this partnership, but he was really getting sick of being under “Snuff” Garrett’s wing and doing kind of lightweight pop stuff like Gary Lewis and Playboys. But one of the projects that came to “Snuff” was this garage band out of Dallas and Mark Benno was in this band. So those guys go to Dallas and produce a couple of singles on them (I think it’s Out There? Yeah, no it’s The Outcasts) and then eventually they come to LA. Mark Benno basically just goes to find Leon and he ends up living in Leon’s house for a while even before Leon even knew he was there [laughs]. But the guy ingratiates himself because Leon was already impressed with Mark as a singer and songwriter in this band that he had been producing. So Leon’s like “who are you? What do you wanna do?” And Mark is like “I want to do a record with you, what do you got?” As simple as that. So they formed a sort of partnership; it’s really more like Benno was his muse and really encouraged him because Leon was kind of insecure. So this guy was building him up and saying “You’re as good as Dylan, you’re as good as the Stones, do your own record,” and Leon had a world-class studio in his own house built by Bones Howe, who recorded and produced for Lou Adler, and a bunch of stuff, Janis Ian, they ended up recording the Asylum Choir so that was a big project and that was sort of the ’67-’68 period. And Leon was doing all kinds of cool psychedelic problems including Daughters of Albion which it’s a really cool record, another duo, nand that sorat of dovetailed into Delaney and Bonnie and beyond. And then Benno became a sideman, he plays on LA Woman by The Doors and then he did some touring with Rita Coolidge and all those people. You see he has all these music credits… But then he went back to Texas and he formed I think [untintelligible] Band and in fact he had a young Stevie Ray Vaughan on it for a bit. I mean, Benno is a real blues hound, he was looking for Lightinin’ Hopkins at one point, he’s just fascinating guy, his books are really fun.

TR: So he has books? So did they all play all of the instruments on Asylum Choir?

BJ: A book, I think it’s different versions of the same book yeah. Like [Andrew Loog] Oldham’s book.

TR: So did they all play all of the instruments on Asylum Choir?

BJ: Yeah, I mean Leon played like 90% of it. In fact, he was even coming up with versions of drum machines back then, ways to loop percussion and do that stuff. He was a real innovator to the extent that he actually was the guiding force behind Roger Linn’s drum machine in the late ‘70s. And Leon had the prototype that he bought from Roger; Roger had been in his band and had been an engineer for him. I talked to Roger Linn and he gave Leon a lot of credit for coming up with that idea of a programmable drum machine.

TR: What do you wish a journalist would have asked you about on this book? What are you really dying to talk about as you’re doing interviews for the book?

BJ: You know, I don’t really know. I’m just glad you’re highlighting the amount of research that’s been put into it and the number of people I talked to. I mean, I think I did 137 interviews. And then navigating the family stuff was a bit difficult, so-and-so saying I don’t want you talking to so-and-so, that’s all interesting. There’s really nothing that jumps to mind.

TR: Again, I just love the book. It’s such a gorgeous x-ray of the scene and the backstage happenings that are really essential to making sense of the surface and peeling back the layer a little bit and seeing how these musicians actually worked or what the network was like. I don’t know I just found that all really fascinating and I appreciate all the work you’ve put into this. We’re in a really golden phase for music books right now, Dilla Time, the Chuck Berry bio, Lenny Kaye’s book, it’s called Lightning Striking, it’s gonna be the new history of rock and roll, and it’s got all these strikingly, really helping us rethink the history of rock’n’roll right from the inside, he’s participant, observer… so congratulations.

BJ: Thanks a lot.

TR: Thanks so much for your time.