An Interview With Steve Matteo

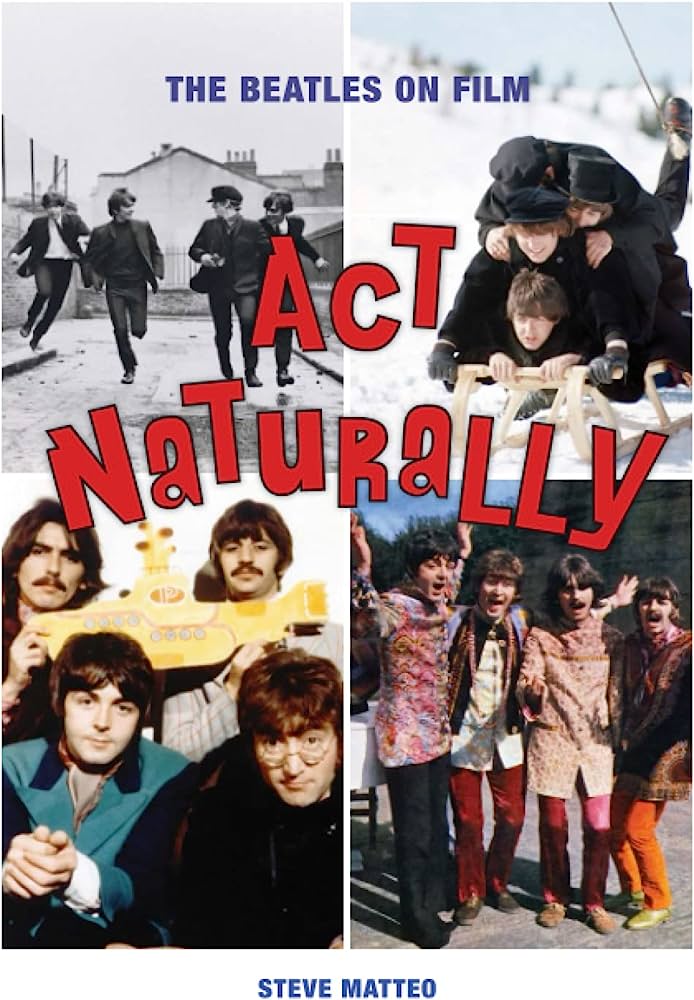

Act Naturally: The Beatles on Film (Backbeat Books, 2023)

TR: Hey, Steve. I’m happy to talk to you after so many years. You remember we had a conversation… god, it would be like so many years ago now.

SM: Yeah, when my Dylan book probably came out. I think that’s when we initially connected.

TR: I remember also talking about your Let It Be book.

SM: yeah, nineteen years ago for the Let It Be book.

TR: Yes. I remember that book to be very important. I really liked that book. Very important for my research and you were very helpful. I remember I have a very positive memory of that conversation. So let me just apologize up front, I haven’t had time to read the whole book. I’ve started it and I can’t wait to read it, but the more blanks you can fill in for our listeners, the better.

SM: Sure. I know it’s a long book, I get it [laughs].

TR: But I did listen to this other podcast you were on that was really, really helpful and gave me a really good idea of what’s in there. And I’d like to start with your Let It Be book and then what you’ve done between that book and this one and how that influenced the way you approach this other material? I’d also really like to talk with you about Peter Jackson, the content of this book, The film’s the new material, given that you have the resources. And then, have you heard this new track?

SM: I haven’t heard it, but I think I can give you some news updates.

TR: I’ve seen some of the updates, but I’m going to be really jealous if you’ve heard the track.

SM: No, I don’t have any inside information [laughs].

TR: Okay, good. So talk to me, what led you to the Let It Be book, and then why did you do a second book of The Beatles? You’re one of these people who’s got two books, right?

SM: Two books on the Beatles and one on Dylan, yeah. Well, I think that what happened is I did the Dylan book, and then I heard about this series, this 33 and a Third series. And I contacted the editor, David Barker. And this was early on, he was really interested in having me do one of the books. And so he said ‘“Would you do a book on Dylan?” And I really didn’t want to do another book on Bob Dylan. At the time, I felt like I had kind of done it to that point, because the Dylan book was sort of a straight biography. It was a coffee table book, but it was a book that really brought Dylan up to that time period. So I really didn’t want to go into that again. So I said to him “Well, what about the Beatles?” And he said that would be good. And I think when I said to him that I wanted to do Let It Be, I think he was a little surprised. If I had said, you know, Sergeant Pepper, or Revolver, the White Album… I think it would have been more of the answer he was expecting, but I wanted to do Let It Be because I thought it was a great story, because it was a film, and because it was sort of the end of the Beatles, and the end of the 60s and the bootleg tapes, and Phil Spector. The storyteller sort of took over from the music person and that’s what I just thought it would be. And I guess it kind of evolved where I felt like, you know, Let It Be was a documentary, so I could sort of approach the writing of the book as if I was sort of making a documentary, and I liked that sort of form because I’m really a journalist first, I don’t consider myself a critic. So that’s kind of where I went and it was very different in that I interviewed a lot of people for the Let It Be book and I think I used a lot more sources. And it was somewhat more analytical. And the book has had a really long life, I think mainly because it’s a book on The Beatles and because of the fact that it’s part of a well-regarded series, which I feel privileged to be part of. And I think it’s evolved over the years, it’s changed. And as different people have become the editor of the whole series, I think it also changed. It was a dramatic change when David Barker left, because I think the sense was to sort of make it younger and to freshen it up and bring it a little more up to date. And then I had a couple of false starts on some projects, some ideas. Actually, believe it or not, there was a point where I thought about maybe doing a book on Bob Dylan and the band together, and what they did, and then Sid Griffin came out with his book, I think it was on the Basement Tapes, and I sort of said: “I think maybe I should pass.” I’ve kicked a few other ideas around, like a book on Pink Floyd and more recently a book on Eric Clapton, but in the last few years, I’ve really started to get deeper again, back into being a Beatles. I think that the Sergeant Pepper 50th anniversary reissues sort of kick-started my blood for that. So I thought about how I really loved the idea of how movies, film, music, and popular culture sort of evolved. So I thought, you know, there really hasn’t been a book on the films of the Beatles in a while. So I thought that would be a good idea and then I ran into an editor that I knew at the 2019 Book Expo —because for about the last 20 years I had been working full-time in the book publishing industry— and I told him about my idea, because he had always kind of kept up with what I was up to, and as soon as I told him my idea, he was just in love with the idea of doing it. And so that was May of 2019 and the book was published, in the States in May of 2023. It comes out in the UK on July 15. So from concept to publication, it was really four years. You know, I didn’t see COVID coming, I didn’t have a crystal ball, but that sort of helped me because we were all in lockdown. And so do I have a book to write, you know, and I’ve got 180 books on the Beatles sitting in one of my rooms here. And the virus sort of delayed the pub date a couple of times, which allowed me to go deeper into the book, and it became a much longer book than we originally envisioned.

TR: So tell me a little bit more about the first book, what you thought was the most surprising source you found for it, and what your thoughts are around that first cut of that movie? What we call the original Let It Be now. And then I want to hear your thoughts on Peter Jackson, but tell me about the sources for that early book and which ones surprised you.

SM: Well, I think the sources themselves maybe didn’t necessarily surprise me, but the thing that did surprise me and bore fruit with Get Back the Peter Jackson series is that I’d interviewed one of these guys, who was around while the filming was going on for Let It Be and he said that it wasn’t all gloom and doom. He said that John Lennon would literally walk into a room and people would just fall down laughing because he’s such a cut-up. So it wasn’t this horrible dour thing that it’s been painted as all these years. So with the idea of Get Back coming out, was going to present a different kind of face of it. I knew that that wasn’t just a gimmick or just trying to rewrite history because my research on the Let It Be book revealed that to me. You know, at that time, there were a lot more people around to sort of interview that were still kind of willing to talk. I talked to some of the same people with a different approach for this book —I interviewed Michael Lindsay Hogg again, I interviewed Anthony Richmond who was the director of photography, who’s had an extraordinary career in film and has worked with everyone you could imagine, I talked to some of the people who were involved with Abbey Road— but there were people that I didn’t talk to again because they weren’t around or they just really weren’t doing interviews. I did try to create a little more context with this book and talk to people who weren’t just involved specifically with the Beatles films or recordings or with Apple because I wanted some real context. I wanted to have a little bit of a broader canvas. So one of the first people that I contacted was Cameron Crowe, because I thought who better to talk about music and movies and rock music than Cameron? And you know, he signed on right away and was like “Sure, I’ll definitely do this.” It wasn’t hard to convince him to be interviewed, although I imagine he’s constantly being asked to be interviewed. I also got Ralph Bakshi, who did Fritz the Cat and he was one of the first guys to sort of do animated films for adults, so Yellow Submarine for him was a real touchstone. Because here’s this movie that’s an animated feature film that’s not being made for children and I thought he would be a perfect person to talk to. So I made sure I got in touch with him and we had a great interview. So and then I just talked to some of the people who were just kind of around and there were people that I interviewed and talked to over the years since I did the Let It Be book that were perfect for this book, like Robert Freeman, you know, who shot so many of the album covers, who is someone who had so much input into the sort of iconic visual look that we’ve all come to see of the Beatles, and obviously, he was part of A Hard Day’s Night, the end title sequence, I guess they call it? That’s his work.

TR: Oh, I didn’t know that. So he did all those photobooth strip things?

SM: Yeah, I think there’s some kind of name for it. I forget what it is. And I mean, what it is basically is the Hard Day’s Night cover, the UK cover, so I went back to that interview that I had done with him. Billy Preston was another person that I didn’t talk to in time to do the Let It Be book, so I was able to get him in there, and he was perfect to lend some more sort of context and background to it. So the intention of this book —and I know, different books have done different ways and I know the significance of sourcing— but I wasn’t looking to go out and interview 300 people, because there are 300 people to go out and interview. I mean, first of all, Paul and Ringo and not going to talk to me. I won’t even ask them. They’re not going to speak.

TR: Well yeah, and they’re not very good sources, either.

SM: Well, I mean, we could certainly debate that one way or another, I’m not going to agree or disagree necessarily, but what I really wanted to do is my research. And I wanted to write it. I wanted to write the story the way that I wanted to write it, which wasn’t a straight linear “They made A Hard Day’s Night, and then they made Help! and then they made Magical Mystery Tour…” I wanted there to be a lot of context and a lot of connective tissue in terms of what else was going on in British film and what else was going on in pop music and rock music as the culture was evolving. I wanted to really get into the relationship of the Beatles and how they influenced the 60s, but also how the 60s influenced the Beatles. So there’s a lot of going back and forth in the book. And I just wanted to do that because I don’t think anybody else had really done that, at least not to the degree that I wanted to do it. I really wanted to take a deep dive into it and I didn’t want to write a book that was just for Beatles fans. Although I’m really pleased with the sort of reception that the book has received thus far in the Beatles community; it really has been embraced and, you know, that’s important to me, because I want it to be accurate and I wanted to add something new. And I always know that there’s a sense of what you do and the only way to add something new is to get original sources and or uncover some deep dark secrets from the past. I mean, it’s just pop music here, we’re not going back and rewriting the Warren Commission report, you know what I’m saying? So I think that was the intention I wanted to make. It’s a film book and I think that people know me as somebody who writes about music. And if you say you’re doing a book on The Beatles, the assumption is that it’s a music book, but I think it’s very much a film book. And not to sound like Captain Obvious, but I straddled the line in that I wanted to make sure there was enough depth about the way the songs were written and conceived and recorded, and the various versions that have come out over the years. I think that was the other thing that I wanted to do with this book because there have been some great film books on The Beatles —I’m thinking of the Roy Carr book which is really a beloved book in terms of not just the writing and the research, but it’s a beautiful looking book with a lot of memorabilia and album covers and singles, covers and photographs— but there have been all these reissues of the films on DVD and blu ray over the years. And I wanted to bring that material into it, I thought that was important, the way the films had been preserved, you know. I talked to the Koch family, who owned all the rights to A Hard Day’s Night and all the memorabilia and everything connected with it and they share the rights with The Beatles for Help! so they’re real curators of the process. And the Criterion Collection folks, I spoke with them too, because of their current version of A Hard Day’s Night that’s out there and that you can buy. It’s a very sort of curated, bespoke edition with the significance that it deserves to be treated with; it’s not just some music film by some rock band. So those are the kinds of things that I really wanted to do. I mean, I didn’t set out to write a scholarly book, it’s not that, and I didn’t set out to write a critical analysis, and I didn’t really set out to write something that was going to be just chock full of brand new news. I wanted to synthesize a lot of information and data and material and just create something that I think was different than what’s been out there.

TR: Alright. So I’m really curious about when you talked to Michael Lindsay Hogg. You talked to him twice, right? Did you come back to him?

SM: Yeah, some years later.

TR: So what did you want to find out from him the first time and the second time you talked to him? Had Peter Jackson come out yet? Or was that really on the border?

SM: The second time I talked to Michael was after the series had been aired and I had a chance to see it. And, you know, Michael is one of these sort of Renaissance people. I mean, his work on Ready, Steady, Go is so significant to the visual look of rock music and pop music, and, beyond the sort of work that he’s done on the music films, he also worked on Brideshead Revisited and he’s done feature films, he’s done theater, he’s an accomplished painter and photographer… he’s royalty. But he’s the nicest guy in the world. He’s just a lovely man. And he’s so open and generous with his time and genuine about what he does. I mean, there are not too many people left around like Michael. I had a chance to meet him a couple of times and spend a little time with them and he’s just, he’s extraordinary. So I mean, this time around, it was really mostly to just get a sense of what he thought of Get Back and what he thought of Peter Jackson. He and Peter Jackson, it’s sort of a mutual admiration. I mean, they both have tremendous respect for each other, so Michael was comfortable with what Peter did. And Peter wasn’t going to even do it unless Michael was good with it, you know what I’m saying? And they had a steady dialogue all the way through the making of it, and I think that dialogue continues. These are people who truly approach what they do from the heart, and it’s the filmmakers and their artists, and they respect the legacy and they respect that they have had such a significant involvement with the Beatles, you know? And they’re fans but they’re not “Fanboys.” So it was great to get that sort of context. Again, I tried not to think too much about what Michael and I talked about the first time around, I just wanted to be like a brand new interview, I wanted to just approach it fresh. I talked to him pretty late in the process, for obvious reasons, because it’s the last part of the book. I think Michael also had some health problems, so there were some times when it was a little tough to get a hold of them, but it was still great. And, you know, Anthony too. I talked to him so much more this time around and this interview was a little bit more in-depth. And, even though it’s been a long time since we talked, we already kind of had established the relationship this time around. He’s worked with —and I say this in the introduction— like, every major British film director that you can imagine since I believe the 50s. So he was great because he’s a strict film person. Meanwhile, he’s worked on movies with David Bowie too, so it was great to get his insights, but I didn’t want to bog the book down too much with he said, she said and I don’t mean that in a derogatory way. I really wanted it to be sort of taking everything and then synthesizing it and then sort of laying it out again, but maybe not as documentary style as the Let It Be book. You know, it was not easy, and I think the Let It Be book wasn’t easy either, but this book was a really large canvas.

TR: So remind me, I’m not sure if I’m just not remembering, but I’m very curious if in either book, was there ever any suggestion that Lindsey Hogs cut off the movie? That the Beatles asked for any revisions in his cut?

SM: Yes. I think the one particular thing that stands out —and I don’t believe that this is really breaking news to anybody— is that early on, when the Beatles were all shown an advanced cut of it —and I don’t think this filtered down from the Beatles to whoever at Apple— three of the Beatles were saying there’s too much of them in this movie and the person that they’re with if you can read between the lines (not sure I understand this?). Now, I’m not saying that necessarily as a criticism, or that I’m agreeing that that was a problem or disagreeing, it’s just what happened. You know, I don’t think that’s necessarily a slight against John and Yoko to be frank. I’m sure there were other little things where it was like why did you do that? Or you should have done that? But I think for the most part, early on, when George Martin was there, the Beatles would reach a certain stage in the recording process, where they would sort of say, “Okay, we’re done. You guys take care of it. You mix it, you master it, you band it, you do whatever you guys do.” But obviously, as things went along, the Beatles became more involved in every aspect of the album, they were in control. They were in charge, those four guys, the four-headed monster, as they were sometimes referred to by the people who were on the inside of the storm.

TR: I mean, the Yoko thing sort of makes sense, but it’s less interesting to me. The thing I’m really curious about is the reason that the sessions got dubbed as dour and downbeat is sort of the falling apart because that movie is cut. Like, the first two acts of that movie are kind of boring. I mean, we would never expect for Beatles sessions to look like that. And then they get up on the roof, and it’s like, oh my God, there it all is. It’s all completely there, they just have not been revealing it to the cameras. But I’m very curious how know they signed off on this cut for this movie and I think that Peter Jackson’s cut actually shed some very interesting light on Michael Lindsey-Hogg’s original cut. Why did that first movie make it out the way it did? It has always baffled me.

SM: I’ve been deeply fascinated by it, but there’s a lot to unpack there. And I’ll try to see if I can sort of condense it. First of all, I don’t think that by the time the film was going to come out and a final cut was ready, they were sort of done. They were kind of like “We don’t even care. We were just finished with this thing.” It was it was Allen Klein, who was like “We owe United Artists a movie and if we put out a movie, there’s going to be a soundtrack album.” And he cut a new deal with EMI because he needed to get some product out there. That’s what the Hey Jude album is all about. It’s Klein saying “Okay, we have a new contract. What do we do? We got to get some product out there, we got to make some money.” So this is part of that. And they’re sort of done with it at this point. And I guess that Michael sort of wanted to show, hey, these guys, they’re breaking up, and this is kind of what’s happening here. And if I think in retrospect, if you wanted to do it over again —and it would have to be a much longer film— you would have to show a lot more of this sort of happy stuff that went on at Apple. I don’t think that back then people had the stomach for sitting through eight hours of The Beatles sitting in a recording studio.

TR: I completely agree, but the original film is what gives people the idea that these were very depressing sessions, right.? And that’s where that starts. And we know from Peter Jackson, that there are all these wonderful exchanges and that Hogg had access to all of that stuff, he just didn’t use it. I think it’s really interesting how he assembled that and how, yes, I agree, they are sort of like resigned at this point, because it’s 1970 and they’re basically like, it’s just over.

SM: It’s over, the [unintelligible] album is out and all of that controversy, you know, and I think he’s like “Well, how long is this movie going to be?” And okay, Twickenham is a film studio, so I’m making a film, but then we get to Apple in this cramped little basement, this makeshift studio. I can’t get completely into Michael’s head, but in talking to him, I think that’s kind of part of it. It’s like “Get this thing out,” you know what I mean? This is what happened with the Rock and Roll Circus too —and although Let It Be did come out right away— Rock and Roll Circus sat in a can for decades and didn’t come out for 30 years or whatever. So, I think there was a sense of we show them what happened at Twickenham, and the studio stuff, we’ll show that after or before the rooftop with these acoustic performances. So if it’s in the studio, we’ll show these finished pieces, rather than more of the Twickenham sitting around and wondering “Well, what are we doing?” I think there’s that sort of dramatic sense in the beginning that they’re just kind of noodling around. And by the time they get to Apple, and it gets close to the rooftop, and they start getting close to some finished recordings, then it becomes like you’re in a recording studio. I think Michael is a filmmaker, you know what I’m saying? So, you bring up Let It Be; I remember when I had a chance to interview David Crosby, and everything was going along great until I brought up Woodstock. It’s like “No, we’re not going to talk about Woodstock again, you have got to be kidding me.” So it’s like you get to the part of the conversation where you bring up Let It Be and they don’t want to talk about it because it’s the end. And, you know, all the bad blood between Paul and George, and Paul quitting, and John said “First of all, I’m going to quit and they’ll keep it quiet.” And then Paul quit and John was like “Well, good. I’m glad you said it. But gee, I should have been the one to say it first.” So we could go back and forth with all of that. So some of that stuff becomes a lot of inside baseball and it becomes a lot of he said she said and which camp are you in? Are you in the Paul camp? Are you in the John camp? Or do you subscribe to the Philip Norman philosophy? You know, there’s somebody who wrote a whole book about the Beatles and what the different agendas and camps are and all that, but I really tried to avoid that. And you know what, sometimes people want to engage in armchair psychology and get inside the heads of these people, or they think that they know more. A person knows more about John Lennon than Paul McCartney does, or vice versa. So these two guys lived in each other’s pockets for 10 years or more, and there are people who come along and seem to think they have more of an insight into the relationship.

TR: So just one more piece of slightly insider baseball, but I’m just curious what your research shows. I mean, I think it’s very dramatic in the Peter Jackson film; you get actually up on the roof and you see that they’re just beating these cables down four floors to the basement, where Glyn Johns is monitoring the live performances and they go back and they listen to this playback. As far as I can tell, the myth is true that there is no sweetening on any of those live tracks. Is that your sense?

SM: Well, I don’t think that anything that we ever hear, whether it’s the Let It Be album, or whether it’s the Let It Be Naked, or the boxset —other than outtakes— any of this stuff is just absolutely left alone. I mean, there’s stuff that, while it’s being recorded, they’re sweetening it on the fly. And then I think that there are things that they go back to later. And they tweak things here and there, they slow things down, they speed things up. They add a little high end, if Ringo’s strums don’t sound right, they boost that up. I mean, it’s just the nature of things.

TR: Yes, I agree. But I want to talk about sort of, you know, a grade sweetening, which would be like overlaying a new guitar line, right? And B grade or C level, which is, you know, making sure that you’re hearing the tom tom in proportion to the snare, those kinds of adjustments, which I wouldn’t really call sweetening. But my sense is that they do not sweeten any of that rooftop concert, they do not go back and add a new baseline or fix a vocal.

SM: I’m sure that there’s tons of sweetening going on. I don’t think they’ve necessarily added a new guitar or something, but I think that they had this remix [unintelligible]

TR: Oh, yeah, I understand about the Demyx stuff, but that’s all it is, right?

SM: From what I remember, I don’t think there’s like a new vocal or a new guitar part or any of that stuff. But I don’t want to say that 100% because I don’t have my research right in front of me.

TR: But there don’t seem to be any sources that say that there was—like with the Shea Stadium where they had an overdub session, like, we know that right? That’s on the books. But for the rooftop, it’s like that’s it. They took what they could get. Obviously, Jackson helped enliven and clarify and separate, all of that. He developed a new digital strategy and that’s where we’re going for all of the future of the catalog. But I still think it’s rather phenomenal that they went up there and it was, what 40 degrees, right? And they’re playing all this stuff live and it’s going straight to tape. That is absolutely astonishing.

SM: I know, it is. But there are musicians who will listen to that, you know, people who have made a living from being a musician, and they’ll listen to it and they’ll say “Oh, there’s a bad note there.”

TR: But that’s part of the charm of it actually.

SM: Right.

TR: Like for Dig a Pony, the starting tempo is very different than the ending tempo and that’s just a natural thing to do, right? They’re just speeding up because they’re excited. But it’s not like that’s a flaw, at least not in my books.

SM: I tell you what it took for me to answer this 100% accurately on the fly on this phone call. What I would say is this: go to the box set that Apple put out of the Let It Be album, and in the notes, they will tell you if this part was in the film and where it was changed. That’s what I’m gonna guess. And because the notes in there are pretty detailed, you should see it.

TR: I’ll check that. One of the things I really liked about Peter Jackson is it says this, this version, this cut, actually winds up on the Let It Be album. And then you can actually do some decoding like, okay, so now we know about Spector, this is what Spector had, this is what he might have done. Right? Anyway, very, very interesting stuff. So let’s talk more about the current book and some of the revelations, some of the new stuff you found that got you really excited about what you were going to put in there that people didn’t know before?

SM: Well, one of the people that I talked to was one of the camera people on Magical Mystery Tour and he talked about how this sort of chaos was kind of refreshing, that he was someone that was used to working on regular sort of linear films. And he found this kind of “Let’s make up a show on our own here on the fly” attitude really fun and exciting. He thought it was great. And this is a guy —I think Michael Saracen was his name— that has gone on to and still makes movies and is still involved with major motion pictures. He said it was very much Paul. So I thought that was really cool, because I think that the Magical Mystery Tour film was met very negatively for a variety of reasons, I don’t think we need to kind of rehash them all here, but in retrospect, I think we see that movie through different eyes now. I mean, I think some of us see it through kaleidoscope eyes [laughs]. But I think it’s a very sort of avant-garde film and I think that it’s kind of a series of set pieces. So it’s another sort of step towards what ends up becoming music videos, which I think is something that is significant. And I think it has just become one of those cult movies for people of a certain generation. I mean, when they saw the film for the first time at the midnight movies, the cult movies, the drive movies, it becomes this thing, which sort of transcends it being a Beatles movie or being a movie that initially was kind of a problem. A lot of my research on the Yellow Submarine part of the book was through the Bob Hieronimous books. He wrote two books on Yellow Submarine, which are the definitive books on it, that’s a life’s work in there. I mean, he really brings out the significance of the collaborators, of all the people that worked on the film. And that was another thing I wanted to do; I wanted to give to the filmmakers, to the other people, not just the Beatles, not just Richard Lester, or Michael Lindsay-Hogg, but the camera people, the actors, the actresses, the writers, the cinematographers, all of those people that should also get there due. It’s significant how many of them were part of the important British films of the 1960s and how many of them have gone on to have long careers. It’s amazing how many people worked on those films, who then went on to work on the Harry Potter films, The Lord of the Rings films, the James Bond films… I mean, we’re talking about the most iconic movies that have ever been made since World War Two, and so that was a revelation to me, the quality of the people. This wasn’t just like “Oh, get a bunch of people together, we’re just making some kind of pop music movie,” or “We’re just making some druggie movie,” or whatever. Disney movies, children’s animated films, at that point would take like three years to make, whereas the Yellow Submarine was made more or less in a year. It’s extraordinary what they were able to accomplish in such a short period of time. I think there’s this sense of creating something brand new that had not existed before, and I think that it was so much of what the 60s kind of ethos was about. Like, we’re not going to focus group this, we’re not going to sit around worrying about it, we’re not going to make sure that it’s already been done 100 times and sell the rights to Japan or whatever. It was like let’s just do it, and let’s try new things, and let’s experiment, and let’s see what happens. And here we are. It’s almost 60 years later and we’re still talking about them.

TR: Yeah, and I think one of the things that I did get to in your book was that the DP on Hard Day’s Night had actually worked on a Stanley Kubrick movie?

SM: Dr. Strangelove, yeah.

TR: Fascinating detail. Tell me about that guy.

SM: Well, what’s interesting about him or about those two films is, first of all, they’re very much sort of back-to-back, but you’re talking about two totally different filmmakers with a totally different approach. There was very much in this cinema vérité style, you know, coming from television and making commercials, using fast cuts. “It’s a pop group. Let’s go, let’s just do it. Let’s just make it happen. Don’t worry about it.” And as you know, Kubrick is the master of detail and storyboarding everything, every single little thing. And that’s why he didn’t make so many films in his lifetime, because of the level of detail. I’m sure you’ve seen these films about the making of The Shining in particular, there’s so much that goes on in that film that it seems like it’s nothing. It’s random. You don’t even see it. It’s just going by on the screen. But then you see what he intended to do, and what he did. So you’ve got this director who is working with two totally different geniuses, you know? Everybody knows Kubrick is a genius but I think Lester sometimes doesn’t get his due, I’ve said this in some of the other interviews I’ve done. Because Lester had mostly done comedies, I think sometimes he doesn’t get to due that he deserves, which is the same I think for comedic actors versus dramatic actors. So Lester is brilliant. He makes A Hard Day’s Night, then he makes The Knack… and How to Get It, which wins the Palme d’Or at Cannes. The first British film, I believe, since The Third Man to win it, which is decades. Then he makes Help! I mean, literally, it’s like “Oh, I’ve got a little time to kill, I’ll make this movie,” so he is really important. I think that there have been a lot of directors that are really very influenced by him. Soderbergh is very influenced by him, they did a book together where a load of birds interviews Lester, basically for the entire book, it’s a really interesting book. And so Lester, within the world of The Beatles, I think he gets his due. He is the man driving A Hard Day’s Night and Help! But beyond that, I think sometimes people kind of forget that he’s a great filmmaker, you know?

TR: Yeah, I’ve always thought Lester was really interesting. I mean, both the script and the director, they get to that kind of bull’s eyes and the planets just aligned for A Hard Day’s Night. There was this other book that I’m sure you’ve looked at. It’s this book comparing the Beatles stuff to James Bond?

SM: Yeah, I’ve read that book. That’s a great book.

TR: Tell me about that.

SM: Well, I’ll just say this. It’s a it’s two things. It’s a great book, and it takes you right up to today. And, you know, there are a lot of the same people who worked on Beatle movies who worked on the Bond films, and then just the whole influence of the British spy movies on films in general in the 60s, whether they were serious films, like The Spy Who Came in From the Cold or all the spoofs, in like Flint, and all of that stuff. You have this moment where the Beatles and Bond explode at the same time and that becomes sort of the center of the universe. And I talked about this in the book in terms of movies. Hollywood was always the place, obviously, for American films, then after World War Two, you certainly get France and Italy which become important places, not just for film, but for style, for fashion, for photography, for art, and then it kind of moves to England, it becomes London, Swinging London. I mean, it’s a cliché, but it is sort of like everything is happening there, fashion, photography, hairstyles, music… everybody wants to work there. Antonioni goes to London to make Blow Up —and he had made all these great Italian films, he was the master— but he goes and makes blow up in London, and it’s very much about this like David Bailey kind of character, but it’s still Antonioni. You know, it’s quiet parts, and it’s mysterious, and it’s just the scenes of nature and barren landscapes. And, you know, it’s Godard, too. I mean, Godard worked with The Stones, he wanted to work with the Beatles, you know. Again, I talked about this in the book too. That’s how he ended up doing Sympathy for the Devil or One Plus One. It’s kind of two different films; it’s his cut, and the cut that the studio wants to do and that whole story. So he was filming that and they were doing Sympathy for the Devil, and that’s when Robert Kennedy was shot and Jagger had to change the lyrics, you know. So all of this stuff is fascinating, and how it all sort of ties together. I think what happened in the 60s was rapid cultural change, and I think we live in a time now where we live in rapid technological change. I don’t think we’ll ever see seismic cultural change and explosions like we had in the past. I think technology has replaced it, unfortunately.

TR: You know, the first thing that comes to mind is that we’ve totally broken the binary for genders. And this huge thing has happened in the last 10 years. That’s, you know, very similar to what was a cultural upheaval in the 60s.

SM: Right, exactly. And I don’t want to get political, but I think there’s a sense on the right that they want the sexes to be apart from one another. And if you go through history, and look at cultural histories, where you get to the part where they really want the separation of sexes, they want them almost at each other’s throats. That’s usually when that civilization starts to break or crumble or change, not necessarily in good ways, you know?

TR: Yes. Steve, this has been such great material. I will. I’ll drop you a note when this thing drops. And I hope we’re able to help with your book sales.

SM: Thank you. I really appreciate it. And you know, I’ve always admired your work. I pulled out Hard Rain and I pulled out one of your Beatles books today. I have those original first-edition hardcovers. Someday, we have to meet in person because I need to have those signed by you.

TR: Of course. I’d be happy to do that. Okay, to do that. influence on me. Serious works, you know, thank you so much. I appreciate that because I’ve had a blast. So thanks a lot for chatting.