Sample Chapter: The Who

History Ain’t Changed

The Who at Sullivan Stadium

Boston Phoenix, July 21, 1989

WITH A TYPICALLY fervid whimsy, the reunited Who’s set at Sullivan Stadium on July 12 reaffirmed the group’s 25-year-old gift for posing key questions—Who are we? Who are you? Why are we all here (again)?—that will aIways be larger than the answers. The grand rock spectacle they virtually invented had ripened, extended itself well into queasy adulthood, and the set bounded from weighty opuses (like “Baba O’Riley”) to non-entities (like “Face the Face”) with telling gaps in quality. Even those of us blessed with the memory of vintage Who sets came away with our best hopes recharged, and in some ways restored. As a piece of rock history, it was less than riveting and yet far more fulfilling than nostalgia. The evening had the odd afterglow of a long-lost friend whose unexpected reappearance helps to reveal something illuminating about yourself.

Accustomed to controversies about motives, the aesthetics of rock pretension, and any number of self-contradictions (they supposedly gave their farewell tour in 1982 with drummer Kenney Jones), the three remaining band members seem perfectly at ease explaining their latest incarnation. Guitarist Pete Townshend, as always, feels responsible to his fans, and has fewer and fewer qualms about staying rich. Singer Roger Daltrey and bassist John Entwistle were never as equivocal about the band’s demise—after all, Townshend was the one to quit publicly and become an editor and writer at Faber and Faber. Although Daltrey, the most well-preserved of the three, claimed in Musician that he would do the tour for nothing, he quickly added, “Better not tell John that. He’ll want my share.”

What the band knows instinctively, and what the current storm of corporate-sponsorship gripes and misplaced hopes hovering over this tour conveniently forgets to mention, is that the Who always conceived themselves primarily as a live act. The group gained notoriety and pioneered its conceptual pieces by way of the stage: you can hear rough drafts of the rock opera Tommy (1969) tumbling out of Live at Leeds (1970), one of rock’s most durable live sets, and Quadrophenia (1973) takes as its subject the Who’s origins in the art-conscious Mod youth culture, and their affectionate bond with their first fans. Who’s Next (1971) became a classic largely because its songs became cornerstones of their stage show.

As a piece of rock history, it was less than riveting and yet far more fulfilling than nostalgia.

The obstacles confronting this go-round are even more formidable than the death of their human tempest of a drummer, Keith Moon, in 1978, or the tragic death of 11 fans after a crowd crush in Cincinnati in 1979. For starters, timing was of the essence in a touring season that would invite comparison to the Rolling Stones. Then there was the question of the form the group would take, especially considering Townshend’s tinnitus. A steady ringing in his ears prevents the Who from cranking up to their record-breaking Guinness Book decibel level, and conscience prevailed against resorting to the second-rate material they performed on their It’s Hard tour in 1982.

To fill out the sound beyond keyboardist John “Rabbit” Bundrick (who’s been in the band since 1979), the Who have expanded with five horns (the three Kick Horns, plus trumpet player Neil Sidwell and trombonist Simon Gardner), extra percussion (Braintree’s Jody Linscott), and three background vocalists. For those who could never imagine the Who as anything but a titanic rock trio with vocalist, the lineup is formidable and on paper a bit off-putting. But on stage in front of 54,000 fans (most from a generation born after Townshend wrote, ”Hope I die before I get old”), the ensemble spread the music’s energy out, emphasizing just how much the original line-up used to carry on its own.

Granted, to get off on this version of the Who, you had to hear past Keith Moon’s substitute, Simon Phillips (who drums on Townshend’s Empty Glass, Chinese Eyes, and the current Iron Man and is the regular drummer with 801). To his credit, Phillips doesn’t mimic Moon’s volcanic thrust. Instead, he punches kicks with the familiarity of someone who has these songs coursing his veins, and he triggers fills that pummel from high to low tom-toms.

This is an improvement on Kenney Jones’ over-pruned efficiency, but that’s not saying much. Moon chased down fills constantly, sometimes fashioning a climax in every bar just because he could get away with. His melodic war-on-idleness jousted chaotically with Townshend’s robust guitar work, and his perpetual flourishes didn’t detract from the music’s larger shapes (Entwistle was essentially the band’s timekeeper). By comparison, Phillips sounded two-dimensional: by the end of the concert, you came to expect certain shapes to his fills (usually non-triplet top-to-bottom cascades) that only drew to Moon’s inventiveness.

Still, compared with lead guitarist Steve “Boltz” Bolton and his sheepish breaks, Phillips was the linchpin of the 14-piece ensemble. Shoved way off to the left and upstaged by the ever-stationary Entwistle (now a quick-fingered silver fox), Bolton rarely took a lead when he didn’t sound painfully self-conscious. Fair enough—if you were Pete Townshend, would you choose a lead player who might upstage you?

For those who could never imagine the Who as anything but a titanic rock trio with vocalist, the lineup is formidable and on paper a bit off-putting. But on stage in front of 54,000 fans, the ensemble spread the music’s energy out, emphasizing just how much the original line-up used to carry on its own.

For his part, Townshend has played less and less acoustic guitar as the tour has progressed. He remains the center of the band, not only as prevailing songwriter but as the ambivalent provocateur who has trouble admitting to himself how much he loves to let his arm whip through his Stratocaster at the age of 44. He’s always felt uneasy with rock’n’rollantics, even though his spherical guitar strokes are as inimitable as Chuck Berry’s duckwalks. In the middle of Daltrey’s gravelly tour of Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man,” Townshend got a look in his eyes that mixed glee with calculation. Gripping his guitar firmly and raising his right hand, he unleashed several swift, impassioned windmills. The arena was his instantly.

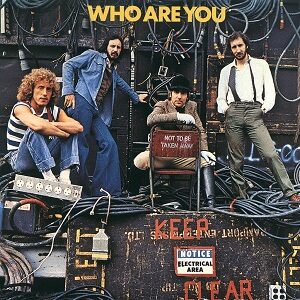

The moment came none too soon: the first half opened almost matter-of-factly with a 40-minute sequence from Tommy, and the initial descending strokes of the “Overture” were enough to send chills of recognition through the crowd. But the set peaked with the roaming instrumentation of “Amazing Journey”; the finale (“Listening to you, I get the music…”) ran out of steam before it got started. Tommy was followed by Townshend’s “A Friend Is a Friend” (from Iron Man, the Ted Hughes storyboard with which he has just thrashed the picayune Andrew Lloyd Webber), a string of early hits (“I Can’t Explain,” “Substitute,” “I Can See for Miles”), and two bows to Entwistle (“Trick of the Light” and “Boris the Spider”) before landing firmly on “Who Are You?”

An aging rock star’s diatribe of self-doubt, “Who Are You?” recounts Townshend’s drunken exhortations to his punk ancestor, Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones. In the song, Townshend is as relieved by punk’s arrival as he is horrified by it, and at Sullivan Stadium, the contradiction gave the band back its potency, and maybe its purpose. The huge video screens lit up with expertly directed close-ups as the sky began to darken, and you could see Townshend grimace at his guitar before it yanked his arms about. The look on his face was furious, as though the punk dilemma still obsessed him, drove him to question his place in rock 11 years on. It reminded you how maniacal Who shows used to be. And the rest of the evening could be measured against the song’s set-closing surge.

After intermission, nothing was the same: the second half dipped and swerved, with mediocrity sometimes subverting greatness, but the best moments (the heraldic benediction of “Join Together,” and a hokey encore Of “Twist and Shout”) more than compensated. Two acoustic oldies (“Magic Bus” and a 1967 sleeper, “Mary-Anne with the Shaky Hands”) did nothing to prepare for near-perfect readings of “Baba O’Riley” and “My Generation,” the latter done without a whiff of irony. Amid grinding pit stops like “Second-Hand Love,” “Sister Disco,” and “Rough Boys,” the set peaked about halfway through with “5.15” and “Love Reign o’er Me,” but then Townshend has always underestimated Quadrophenia’s worth (it’s a contender for album of the ’70s).

With a Tommy performance in New York already earning $1.7 million for the Nordoff Robbins Center for Music Therapy, and another show scheduled in Los Angeles, the Who have already upstaged the Stones in the profit realm. It remains to be seen whether rock groups will ever begin talking in terms of tithing to the less fortunate, the way John Lennon did.

Miller Beer’s corporate sponsorship helps keep this cast and crew of more than 120 people on the road this summer: the show is elaborate but not garish, and the ticket prices simply don’t cover the daily expenses of $50,000-75,000.

Townshend has yet to write a song about hearing loss or carry the subject of aging in rock beyond what he did in songs like “They’re All in Love” or “Dreaming from the Waist” on 1975’s Who by Numbers (curiously absent from Sullivan’s set list). But the larger meaning of this tour turns on how this band redefines itself (as an arena act that plays its youth anthems as though adulthood might never tame them) and how its audience responds (the revolution will apparently not be over $10 parking, $10 programs, and $20 souvenir T-shirts). And if the closing blast, “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” was any index, the questions of generational identity in an era of political upheaval are issues that remain as relevant as ever (updated in everyone’s mind with the daunting specter of China). This is one ’60s group that will not march gently into the late ’80s. For all intents and purposes, meet the new band—same as the old band.